Although there are usually more widows in the world than widowers, little is known about the economic impact of the death of a spouse in different historical contexts. This paper asks the question, what did the death of a spouse mean for women of different races living in Cape Town? A household survey from 1938/9 provides insights into the lived experiences of these widows just before World War II.

Understanding widowhood is an important part of understanding society; the lives of widows offer insights into how households and families are organized and what responses there are to those in need. The loss of a spouse can threaten the functioning of a family unit and can lead to poverty for the remaining spouse and family members (Van Poppel, 2010).

Some have argued that nuclear families experience this loss more severely than non-nuclear families, and widows in Western society have often been characterized as poor and lonely (Hahn, 1992). In societies in which nuclear households predominate, widows are more likely to live alone upon the death of a spouse (Wall, 1992). Others found this was not the case for widows in Africa (Potash, 1986).

Widowhood in Cape Town

Today Cape Town is an incredibly diverse place, and this was already true in the first decades of the twentieth century. Many factors might have impacted households and family formation and therefore the experience of widowhood. The focus of this work is on coloured and white women living in Cape Town. While the term “coloured” is used derogatively in some parts of the world, in South Africa it is the preferred and officially used term (though not uncontested) referring to individuals of mixed cultural and racial backgrounds, stemming from early colonial interactions with indigenous and enslaved peoples and European settlers.

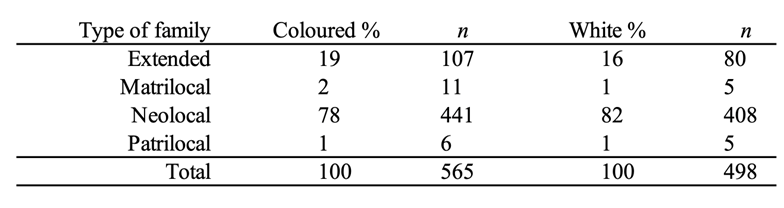

Although the household survey was conducted more than a decade before the formalization of Apartheid in 1948, Cape Town was already a city full of divisions. An analysis of the survey data shows that significant gender and race wage gaps existed, with white men having the highest average earnings of £18 per month, white women earning on average £9 per month, coloured men earning on average £8 per month, and coloured women earning on average £4 per month (Rommelspacher, 2022). Despite these and other differences that existed in Cape Town society before World War II, coloured and white household structures looked very similar, as can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Dominant type of families in Cape Town, 1938/1939.

Source: Rommelspacher (2024)

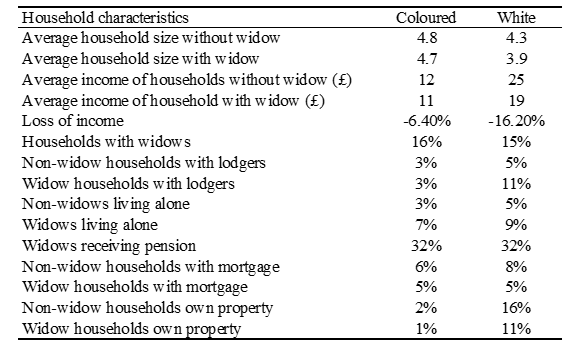

Other similarities included widow’s positions in households, with 64% of coloured widows and 61% of white widows being household heads. This similarity did not mean that widowhood was experienced in the same way by women of different races as white women experienced a greater loss of income in widowhood than coloured women. However, household income was much lower for coloured households in the first place and these households were far less likely to own property than white households.

Table 2. Characteristics of coloured and white households with and without widows

Note: Loss of income is the difference in earnings per person between households without and with widows.

Source: Rommelspacher (2024)

Conclusion

In some respects, white and coloured households looked very similar in Cape Town just before World War II, but widowhood emphasized the differences experienced by women of different races. White widows saw a greater loss of income than coloured widows, though white households had a higher average household income to start with and white households were more likely to rely on a male breadwinner. While white widows resided with their unmarried children and increased their incomes by taking in lodgers, coloured widows were more likely to live with married children, grandchildren, and extended families. Financial constraints seem to have motivated this decision for coloured households, though it is also possible that social norms impacted approaches to widowhood. Widowhood, therefore reflected the inequalities and differences that existed in the city.

References

Hahn, S. (2002) Women in older ages – “old” women? The History of the family, 7(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-602X(01)00095-1

Potash, B. (Ed). (1986). Widows in African societies: Choices and constraints. Stanford University Press.

Rommelspacher, A. (2022) Work, wedlock and widows: comparing the lives of coloured and white women in Cape Town, 1900–1960 [PhD Thesis, Stellenbosch University].

Rommelspacher, A. (2024) What about the widows? Widowhood and households in Cape Town 1938/39. The History of the Family, 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/1081602X.2024.2307538

Van Poppel, F. (2010) Widows, widowers and remarriage in nineteenth-century Netherlands. A Journal of Demography, 49(3), 421–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000148756

Wall, R. (1992) Relationships between generations in British families past and present. In C. March & S. Aber (Eds.), Families and households, divisions and change (pp. 63–85). Macmillan.

Feature image: Florence Louise Josephine Zerffi (1882–1962) Portrait of a woman wearing a white hat, oil on board. Zerffi is one of the widows who appeared in the household survey.

Publisher: Source link