The only Nobel Prize that has nothing to do with the will of its creator, Alfred Nobel, was announced on Monday, October 14th. As usual, the announcement sparked a range of reactions, and as economist Noah Smith points out, this prize has traditionally been awarded to influential scholars within the sphere of economic discipline. This time, the prize did its job and recognized the contribution of neo-institutionalism to economics. Its influence is undeniable, as can be seen from the fact that these authors are widely cited in macroeconomics courses. For instance, Daron Acemoglu had long been mentioned in academic circles as a favorite to win the Nobel, much like Leonardo DiCaprio was repeatedly named a favorite for the Best Actor Oscar. While we are already familiar with the kind of economics that dominates classrooms and the hegemonic media, as well as the economics that influences politics and shapes economic policies, it’s worth discussing the theoretical and empirical contributions being recognized and their main critical observations.

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson (AJR) have been awarded for studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity. Their work addresses what is perhaps one of the most important questions in economics: How do we explain the economic disparity between countries? Why are some nations persistently wealthy while others remain consistently poor? We should understand prosperity as the plain and simple economic growth. If we rule out biological, cultural, or geographical reasons, what remains is dimension of the historical-political order. Development, then, is largely dependent on one key factor: In the early stages of nations, before they became modern states, what forms of government, civil codes, and laws were established? According to AJR, the root of development lies in the different types of political institutions that were established across the world. Thus, inclusive institutions are in sharp contrast with extractive institutions.

Inclusive institutions are those that distribute power and limit its arbitrary exercise, enforcing property rights. In few words: the rule of law. On the other hand, extractive institutions are the opposite: full arbitrariness, little to no property rights, the rule of the strongest. Without the correct institutions, markets cannot function as they should. The rationale goes like this: These early institutions brought with them economic practices that shaped the behavior of both the state and entrepreneurs. Correct institutions encourage the right incentives. Thus, we have the innovative entrepreneur as a product of inclusive institutions, and the rent-seeking entrepreneur as a product of extractive institutions. In short, development is achieved through the institutions of idyllic capitalism: full property rights and democracy.

But this pristine vision of development is vulnerable from many fronts. To start, AJR must empirically prove that their hypothesis is correct — that it is institutions that generate economic growth, not the other way around. To achieve this, they use historical data on settler mortality rates. In principle, where mortality rates were higher, it was harder for Europeans to settle and bring inclusive institutions. In contrast, where mortality was high, extractive institutions were the only option. Glaeser and his colleagues argue that it is impossible to separate the effect of institutions from the effect of settler establishment. For these authors, an equally valid explanation is that settlers brought their “advanced” human capital, which made the long-term difference. In any case, econometrically speaking, it is almost impossible to ensure that it is indeed the institutions, and not something else, that determines who develops and who doesn’t. It could be that the “right” institutions flourished because it was in the settlers’ interest to reproduce the emerging capitalism. Even the mere presence of European settlements facilitated trade flows. Settlers were essentially recreating their societies in the colonies to resemble the metropolis.

Moreover, AJR’s argument lacks originality or, worse, lacks thoroughness in acknowledging intellectual predecessors. The same argument had already been put forward by Marxist economist Paul Baran in the 1950s. As noted by the economist Shahram Azhar on X, Baran mentions in his book The Political Economy of Growth that it matters little who the Europeans settlers were — whether families fleeing religious persecution or expatriated criminals, they all “carried capitalism in their bones and encountered little resistance”. Where conditions were adverse, either due to climate or facing advanced forms of statehood, colonialism was simply looting.

Another criticism is the great variability in the types of institutions imposed in the colonies. These institutions were highly dependent on specific contexts and the economic interests of the metropolis. As Vernengo and Perez-Caldentey highlight, when necessary or convenient, the British had no problem establishing exclusive practices, while at the same time, the Spanish could implement inclusive institutions as well. These Latin American economists also question AJR, and the literature they produced, for placing the market on a pedestal while underestimating the state’s active role in promoting development.

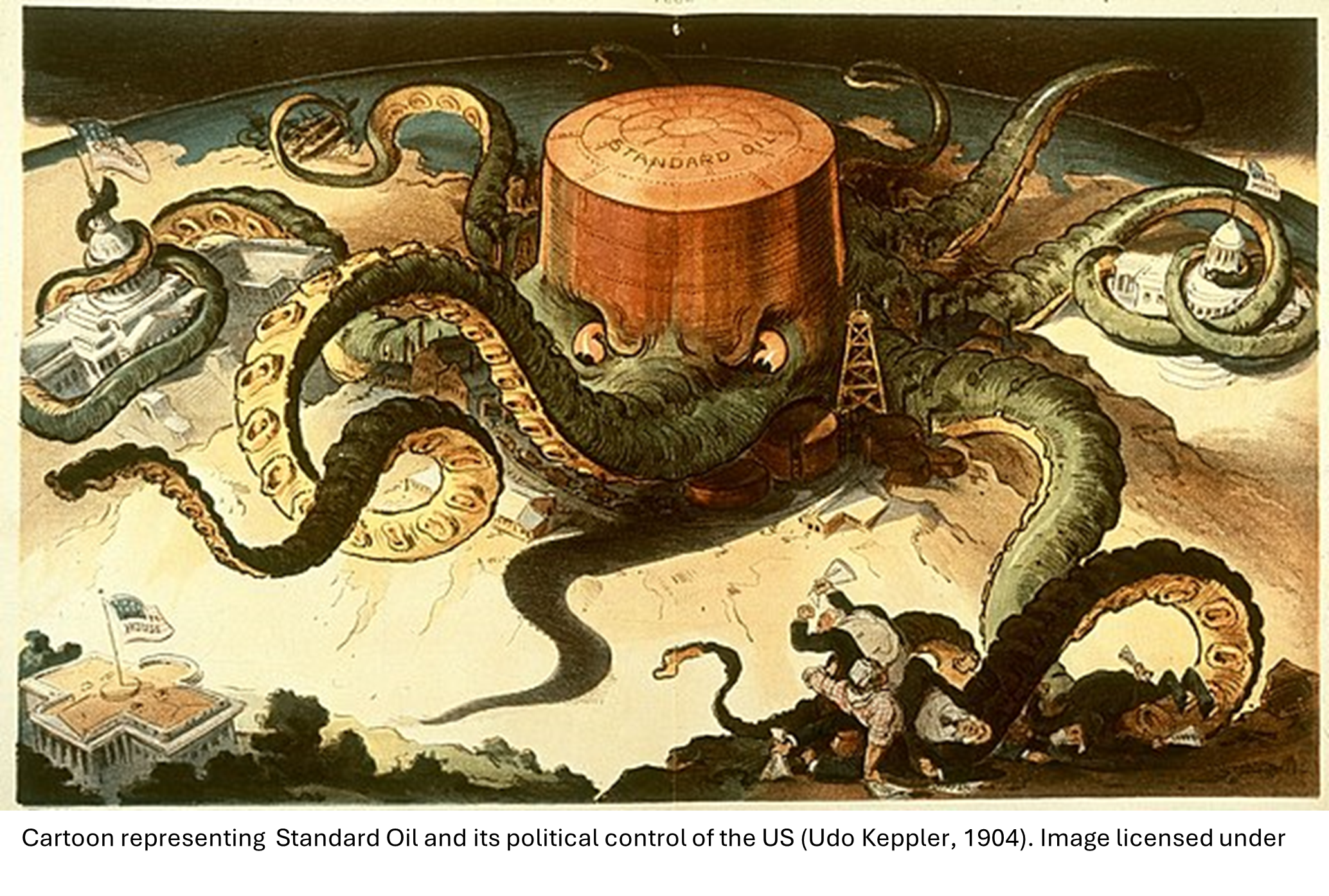

Political scientist Yuen Yuen Ang, author of How China Escaped the Poverty Trap, also questions whether the so-called inclusive institutions are truly inclusive for all social groups. In North American colonies, property rights certainly protected white settlers, but not Native Americans, slaves, or women. As Yuen Ang suggests, the development of capitalism, both in the West and in the East, has been driven by the proliferation of sophisticated forms of corruption. This sophisticated form is called access money: the purchase of economic privileges by those with power. This type of corruption was characteristic of the so-called Gilded Age in the United States, a time that saw the rise of the great industrial barons of the late nineteenth century, who blurred the lines between politics and economics to amass great fortunes. The Gilded Age would also be characteristic of contemporary China. This interpretation of development history is far from AJR’s “correct” institutions.

Another problem is that, beyond using mortality data in their empirical studies, AJR completely ignore the violent nature of imperialism and colonialism. The plundering and extermination of entire peoples are not part of the analysis. The professor of Development Studies, Jostein Hauge, provides some insight into this absence: this is how economics profession operates, from the “intellectual” distance of studying the economy without being “stained” by etical considerations of the subject matter. Furthermore, the absence of an imperialist context and massive violence reflects that AJR focus on a simplistic and deceptive interpretation of development: GDP per capita.

We should note that neo-institutionalism appears as an approach that covers up the loose ends of neoclassical theory. It is therefore a complement to the dominant economic narrative. It does not seek to critically scrutinize conventional theory but rather to save it. For these neo-institutionalists, solid liberal institutions are the foundation of private property and provide the “correct” incentives for innovation, technological development, and competition. On an ontological level, economic actors are what they are, and incentives determine which behaviors will prevail. There is no discussion of how these actors come to be constituted; their nature is already fixed. According to heterodox economist Ha-Joon Chang, this aspect differentiates the new institutionalists from the classical institutionalists, such as Veblen, who laid the foundation for a much richer economic analysis, one reluctant to conceive of the economy as an entity separate from history and society as a whole.

As mentioned at the beginning, the Nobel Prize in Economics is awarded to those who have been highly influential within the discipline. As has happened before, even if this academic community reaches a consensus that does not signify any progress beyond what has already been advanced by other social sciences, that consensus is still perceived as a demonstration of economics’ technical and scientific superiority. It’s no surprise, then, that the laureates’ work contains methodological and factual flaws. Economist David Y. Albouy even warns of serious problems with the consistency of the mortality data used by AJR. Measurement and manipulation issues suggest that the results lack of solid foundations.

The dominant economic literature on comparative development, which seeks to answer the big question of current global economic disparities, has serious difficulties explaining how countries like South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and China can “prosper” despite lacking the type of institutions that supposedly drive development. The acclaimed book summarizing the studies and contributions of neo-institutionalism is written by two of the laureates, Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, and is titled Why Nations Fail. Neo-institutionalism deserves a book narrating its shortcomings as an example of how theories that claim to be rigorous end up being deeply unsatisfactory. Such a book could well be titled Why Theories Fail.

Yaku Fernandez-Landa, originally from Peru, is a Political Economist currently based in Geneva. He has completed studies in Economics and Political Economy in Switzerland and the US.

Publisher: Source link