How did Christianity expand in sub-Saharan Africa to become the region’s dominant religion? Christian missions in the 19th and early 20th centuries were established in healthier, more accessible, and richer places before expanding to economically less developed areas. Christianization did not leave any benign legacy on macro-economic development during colonial or contemporary times but continues to affect human capital formation.

Among the world’s most powerful cultural transformations in modern history has been the rapid expansion of Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa. While Christians made up barely 5% of sub-Saharan Africa’s population in 1900, the region has risen to be predominantly (57%) Christian today, boasting the most committed Christians worldwide (The Economist 2015). By 2060, Africa will be home to 42% of Christians worldwide, by far the largest concentration globally (Todd et al. 2018).

Christian expansion was initially facilitated by missionary efforts who throughout the colonial era provided the bulk of formal education and health care (Frankema 2012, Meier zu Selhausen 2019). On the basis of missionary atlases denoting the location of Christian missions in the early 20th century, a burgeoning literature finds long-term effects of early missionary presence on current African education, health, demography, culture, and social mobility outcomes (e.g. Nunn 2010, Cage & Rueda 2018, Okoye 2021, Alesina et al. 2021). But how did Christianity initially expand to become the continent’s dominant religion and do colonial-era missions continue to affect development outcomes today?

In two recent papers, Jedwab, Meier zu Selhausen & Moradi (2021, 2022) explore the determinants and long-term effects of Christian missionary expansion in Ghana and across 43 sub-Saharan African countries (hereafter referred to as Africa) using a number of identification strategies. For Ghana, we create a new annual panel dataset on the point locations of all mission churches over two centuries: 1751–1932. For both Ghana and Africa, we present causal estimates of the role of malaria, railroads, and cash crops on the diffusion of missions.

Missionary Expansion

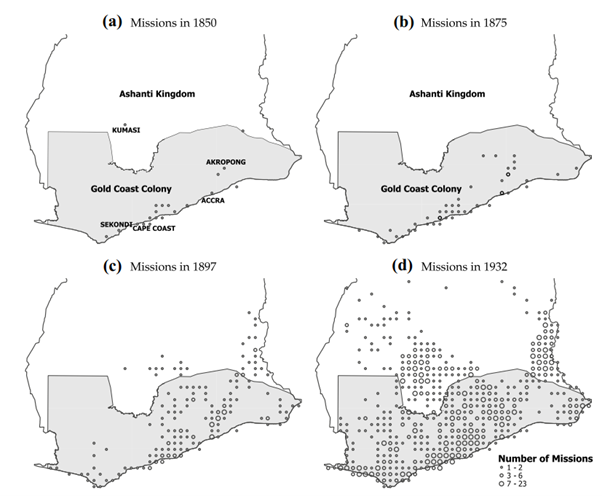

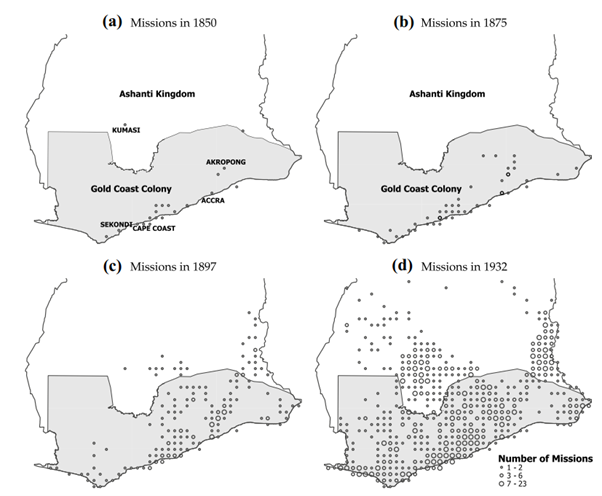

Figure 1 maps mission locations in the Gold Coast between 1850 and 1932. Missions initially settled along the coast, avoiding creating inland stations. The Ashanti Kingdom was hostile to Christian proselytizing, limiting the activities of the various missionary societies to the territory of the Gold Coast Colony (Figure 1b–c). Access to the interior was only facilitated by the rail and road building of the early 20th century. By 1932, mission stations covered large parts of Southern Ghana (Figure 1d), totaling 1,831 main and out-stations.

Figure 1: Gold Coast mission locations c. 1850-1932

Quinine – the Game Changer

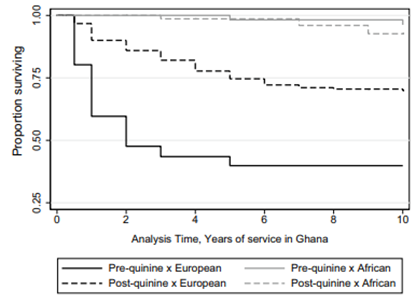

Recruitment and training of European missionaries was costly. Adaptation to the missions’ tropical environment took time. Malaria was the major killer, striking Europeans soon after arrival, making missionary expansion ineffective. Quinine was the game-changer from the 1850s onward. We estimate survival chances and find that after its introduction c. 1850 as both cure and prophylaxis, missionary mortality sharply declined. Figure 2 shows that in Ghana, the likelihood of European missionaries surviving more than 3 years pre-1850 was about 40% compared to 100% for African missionaries. Post-1850 survival likelihood increased to about 80% for European missionaries surviving 3 years on the Gold Coast.

Figure 2: Survival analysis of European and African missionaries

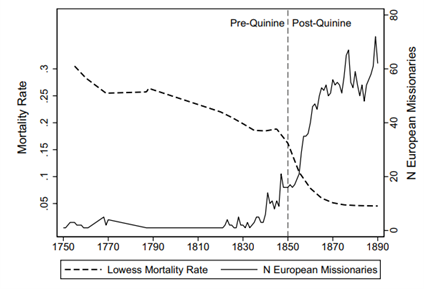

Encouraged by a lower disease burden due to quinine, European missionary staff expanded considerably in number, from fewer than 20 pre-1850 to approximately 60 post-1870 (Figure 3) spreading the gospel in Ghana. However, their numbers always remained below 70. These numbers would never be sufficient to preach to the hundreds of thousands of Africans that converted to Christianity. Employing African converts as missionaries was a much more cost-efficient and effective conversion strategy. Europeans nevertheless kept the oversight and important managerial positions within the Church.

We exploit the timing of quinine introduction in our identification strategy, testing whether missions expanded into areas of higher malaria risk post-1850 vis-à-vis pre-1850. We find that post-quinine missions spread into areas of greater malaria risk, further away from the coast.

Figure 3: European mortality and number of European missionaries in Ghana

Railroads and Cash Crops

We develop two more identification strategies. First, we investigate the timing of railway construction and mission expansion. We show that missions expanded along railroads that were built for commercial and military reasons from 1897-1932. Missions only expanded into an area after the building of a railroad line – not before. Second, exploiting various agricultural commodity price booms and busts we show that missions expanded more into cash crop areas (cocoa, palm oil, rubber, kola nuts). Cash crop cultivation was an important source of African income. Local demand for the gospel was thus greater in richer and better-connected areas. Africans would pay for the mission’s services contributing to the mission supply.

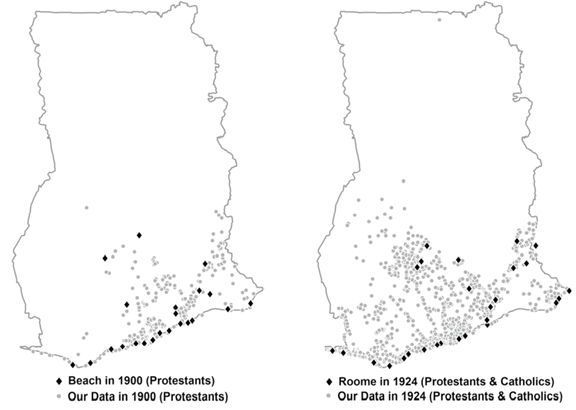

Measurement Error in Missionary Atlases

When comparing our census of missions for Ghana with missionary atlases (for those studying missionary legacies, Beach 1903 and Roome 1925, are the most commonly used examples), we find that atlases omit more than 90% of missions (shown in Figure 4). Moreover, missionary atlases selectively reported early European residence missions located in more developed areas. We confirm this systematic omission for all African countries studied.

Figure 4: Missions in Ghana in 1900 and 1924: Mission Atlases vs. Census Sources

Next, we examine the implications of studying highly selected and endogenously located missions, sourced from atlases, on long-term development outcomes, in particular (log) nightlights in 2010. We find that for Ghana, samples limited to atlas missions generate effects twice as large as those generated by samples from census missions. In addition, when using a rich and historically relevant set of control variables, long-term effects appear statistically insignificant for census missions while endogenously selected atlas missions continue to indicate weak positive statistically significant effects on economic development today. We confirm the results for the rest of Africa.

These results caution that non-classical measurement errors in mission atlases and omitted variable bias may lead to an overly optimistic account of the importance of missions for contemporary development. The use of alternative ecclesiastical sources, the development of appropriate identification strategies, and the use of historical controls predicting mission locations can remedy these concerns.

Christianization without Economic Development

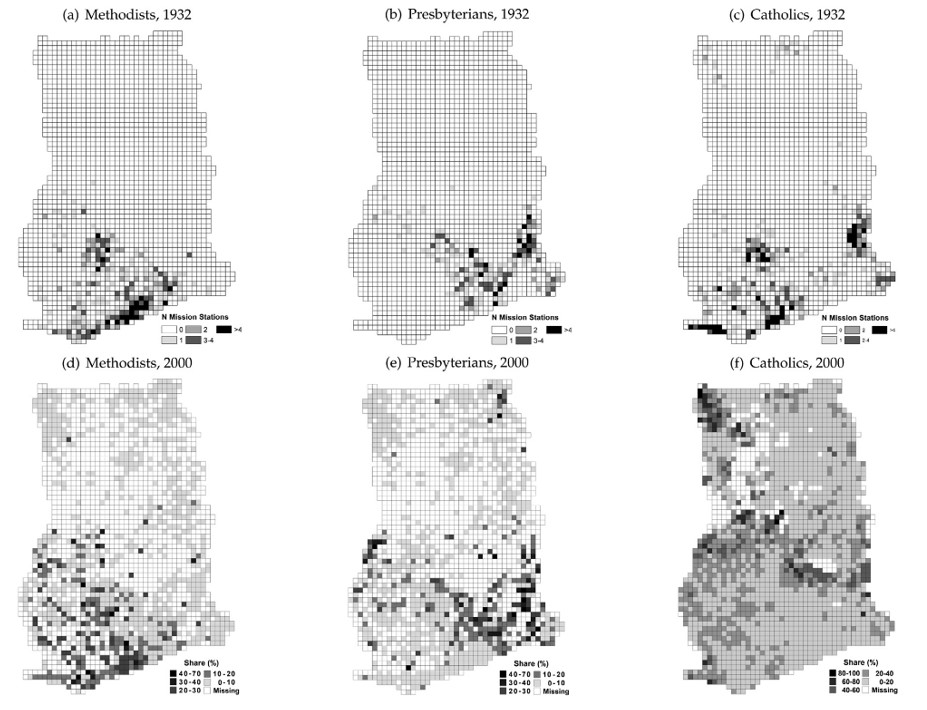

In Jedwab, Meier zu Selhausen & Moradi (2021) we establish that spatial patterns in religion persisted in Ghana over time. Figure 5 (a-b, d-e) shows that today the main Protestant denominations, the Presbyterians (south-east), and Methodists (south-west,) continue to have their strongholds in their former respective spheres of influence that the two earliest mission denominations had established in 1847. The boundary of the spheres remains clearly visible until the present day. For the Catholics, this is only true for the Volta region (Figure 5c, f). The Catholics were late-comers (1890s) and under prevailing Protestant and Muslim competition, they followed a strategy to expand further away from Protestant and Muslim heartlands and today are particularly present in the north-east and outside the fringes of the former Presbyterian and Methodist spheres.

Figure 5: Location and number of mission stations in 1932 and denominational shares today, Ghana

Next, we apply several innovative identification strategies to estimate the legacy of missionaries in Northern Ghana. First, we exploit a “rain miracle”. During the 1932 famine caused by drought in (Jirapa), rain fell during Mass. This was taken as a sign of godly power, triggering mass conversion locally. Today, there is still a much higher proportion of Catholics in that area, though people are equally poor as people residing in less Catholic areas further away. We also exploited the fact that Presbyterian and Methodist mission societies partitioned the Ghanaian territory into spheres of influence. This created (i) significant discontinuities in denominations and (ii) more Protestants due to heightened competition along the boundary of the old mission fields. Despite these differences in denomination, we find the areas very similar in economic outcomes. Finally, we look more closely at Catholic expansion strategies. As a latecomer with strong financial backing, Catholic missions chose to locate away from Protestant and Muslim strongholds. This created spatial patterns that do not correspond to economic activity.

Overall, we found no association between Christian missions and economic development, whether during contemporary (proxied by nightlights) or colonial times (proxied by urbanization). These results are consistent across all Christian denominations, which reinforces our findings. However, some results suggest that Christian missions might have had a positive effect on human capital formation.

It could well be that Christians in Africa are among the most skilled and wealthiest members of society when compared to other individuals within their communities (Meier zu Selhausen et al. 2018; Wantchekon et al. 2015). But the fact that Christianization might have increased social mobility does not automatically generate economic activity. The private returns of being a Christian – which may include increased human capital – might have been larger than the actual social and economic returns. Indeed, in a seminal study, Pritchett (2001) pointed out that rapidly rising educational attainment rates in post-independence Africa have failed to translate into learning and sustained economic growth at the macro level.

Sub-Saharan Africa is becoming the new global center of Christianity. Our analysis of Ghana suggests that Christian conversion will not necessarily promote economic development on the continent.

References

Alesina, A., Michalopoulos, S., & Papaioannou, E. (2016). Ethnic Inequality. Journal of Political Economy 124(2): 428–488.

Beach, H. P. (1903). A Geography and Atlas of Protestant Missions: their environment, forces, distribution, methods, problems, results and prospects at the opening of the twentieth century (Vol. 2). New York: Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions.

Cagé, J. & Rueda, V. (2016). The Long-Term Effects of the Printing Press in Sub-Saharan Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8(3): 69–99.

Frankema, E. (2012). The Origins of Formal Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Was British Rule More Benign? European Review of Economic History 16(4): 335–355.

Jedwab, R., Meier zu Selhausen, F., & Moradi, A. (2021). Christianization Without Economic Development: Evidence From Ghana. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 190: 573–596.

Jedwab, R., Meier zu Selhausen, F., & Moradi, A. (2022). The Economics of Missionary Expansion: Evidence from Africa and Implications for Development. Journal of Economic Growth 27: 149-192.

Meier zu Selhausen, F., van Leeuwen, M. H. D., & Weisdorf, J. (2018). Social Mobility Among Christian Africans: Evidence From Ugandan Marriage Registers, 1895–2011. Economic History Review 71(4): 1291–1321.

Meier zu Selhausen, F. (2019). Missions, Education and Conversion in Colonial Africa. In D. Mitch, & G. Cappelli (Eds.), Globalization and the Rise of Mass Education (pp. 25–59). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nunn, N. (2010). Religious Conversion in Colonial Africa. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 100(2): 147-152.

Okoye, D. (2021). Things Fall Apart? Missions, Institutions, and Interpersonal Trust. Journal of Development Economics 148: 102568.

Pritchett, L. (2001). Where Has All the Education Gone?. World Bank Economic Review 15(3): 367-391.

Roome, W. R. M. (1925). Ethnographic Survey of Africa: Showing the Tribes and Languages; Also the Stations of Missionary Societies. London: Edward Stanford Ltd.

Todd, J., Zurlo, G., Hickman, A., & Crossing, P. (2018). Christianity 2018: More African Christians and Counting Martyrs. International Bulletin of Mission Research 42(1): 20–28

The Economist. (2015). The Future of the World’s Most Popular Religion is African. 25 December 2015.

Wantchekon, L., Novta, N., & Klašnja, M. (2015). Education and Human Capital Externalities: Evidence From Colonial Benin. Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(2): 703–757.

Featured image: Basel Mission chapel at Odumase, Ghana (1870s), Browse (bmarchives.org)

Publisher: Source link