The failure of mainstream development policy to deliver on the promise of eradicating global poverty is increasingly difficult to deny (World Bank 2024). As a result, theories of global development are opening to alternative and critical approaches. In this context there has been a renewal of interest in dependency theory as a rich heterodox tradition of political economy (Kvangraven 2021; Chilcote and Salém Vasconcelos 2022; Antunes de Oliveira and Kvangraven 2024). In a recent paper, I turned to one of the foundational scholars of dependency, Walter Rodney (1942-1980), to work through some of the strengths and limits of dependency theory for contemporary studies (Johnson 2023).

Locating Rodney

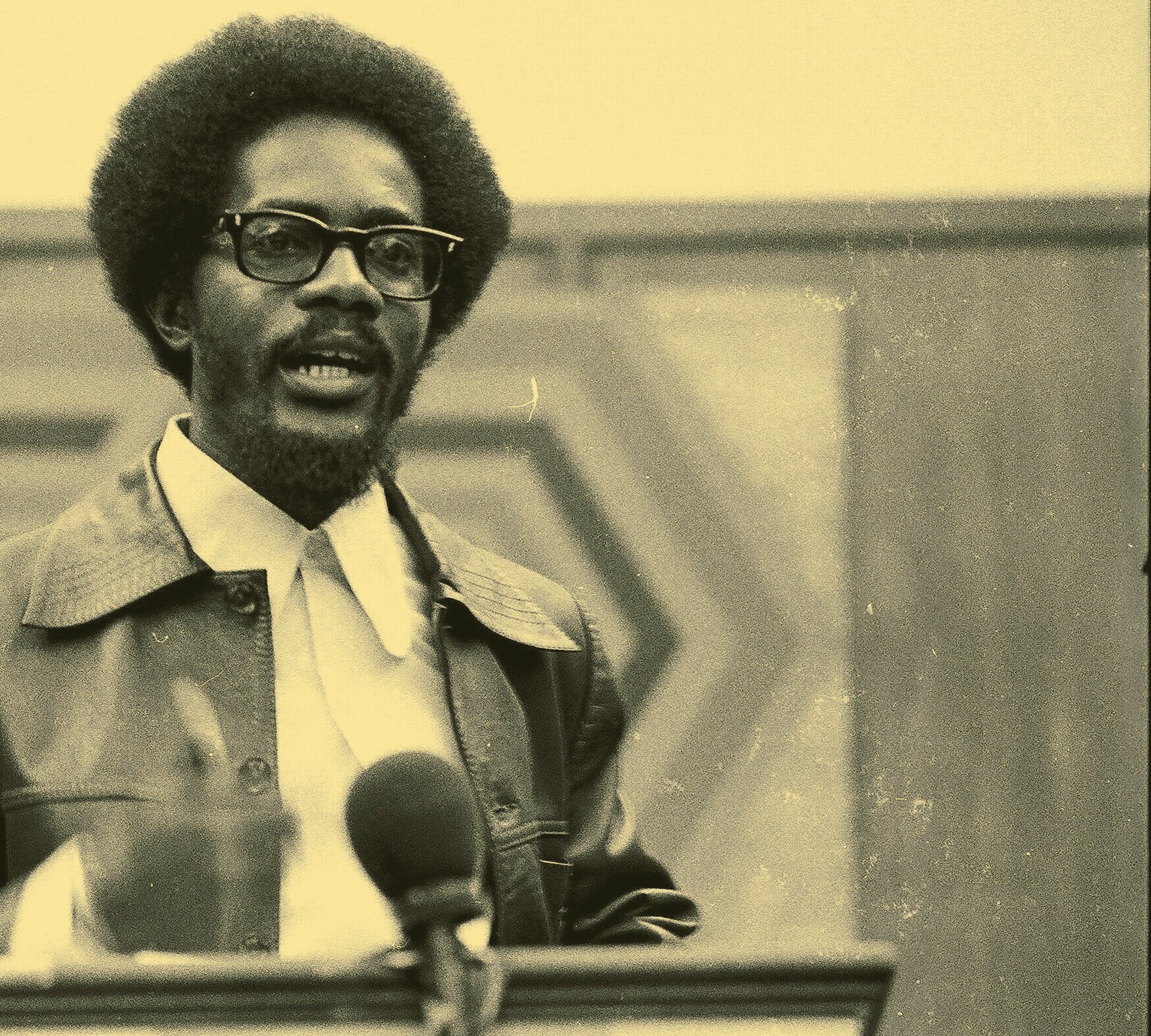

Rodney was an Afro-Guyanese historian, political economist, and scholar of Africa and the Caribbean. He was also a Marxist. However, he treated the resources of historical materialism not as fixed and complete, but as an evolving body of theory and methodology to be developed through concrete empirical research. Rodney wrote a series of major books and essays, both scholarly and popular, and he was a committed political activist. He died much too early in his career, assassinated at the hands of his own government in the streets of Georgetown in 1980.

Rodney’s significance is evident in many fields. As a card-carrying historian with a PhD from SOAS, he is known by historians as an authority on Africa and the Caribbean. His dissertation, published in 1970 by Oxford, remains foundational in contemporary African historiography (Rodney 1970). In political economy, Rodney is best known for his monumental book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972), which was written for a mass audience but is also rightly regarded as a classic work of dependency theory and world-systems analysis (Wallerstein 1986). Rodney is also regarded as a key theorist in the field of Black Studies, and, most recently, Rodney is treated as a central figure in the literature on racial capitalism (Jenkins and Leroy 2021).

Rodney’s work contains many resources still to be recovered and read for the problems of today. My own approach to this was to recover his final book, A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881–1905 (1981), which is scarcely read. The book is neglected for several reasons. Most obviously, it is a painstaking work of primary research, written for specialists on Guyanese and Caribbean history. It does not have the range of his first book on West Africa or the political flair of his most famous book on imperialism and dependency in Africa. Moreover, the book was published posthumously. Rodney was assassinated around the same time that the Third World project itself was assassinated (Prashad 2007), giving way to the neoliberal turn and the debt crises of the 1980s. Theoretical fashions would track this turn, moving away from historical materialism and toward the more culturalist and ideational frame of postcolonial and decolonial studies.

For these reasons, I found Rodney’s final book ripe for retrieval as a work that exhibits a serious and creative application of a historical materialist framework to analyze capitalism and class in a concrete colonial setting. I sought to reintegrate this work into Rodney’s wider corpus and into the context of debates about Marxism, dependency theory, and world-systems analysis in the 1970s.

Three Contributions

I organized my findings regarding Rodney’s work into three main contributions. First, Rodney’s works contribute to the literature on the nature and history of capitalism, and especially the inherently international constitution of capitalist development. Second, Rodney offered a theoretically attuned and empirically grounded account of the central role of unfree labor in the history of capitalism. Third, Rodney mobilized the same framework to analyze the role of race and racism in capitalist class formation and capitalist development.

Regarding the first point, there are basically two conventional approaches within the Marxist tradition to the question of how to conceptualize capitalism as an object of critical study. The first emphasizes domestic class structure and focuses especially on the relationship between wage labor and capital (Brenner 1977; Wood 2001). The second emphasizes the international division of labor and views the classic form of capitalist large-scale industry analyzed by Marx as but one key node within a wider capitalist world system of production and exchange (Frank 1969; Wallerstein 1974). Unfortunately, these contrasting views often breakdown into one-sided polemics in which those centering class and production frame their work in opposition to those who center international flows of capital and labor.

But Rodney’s work does not fit neatly into this division. This is clear right from the beginning, in his first series of studies of West Africa, in which Rodney analysed the formation of the European slave trade by centering the question of class formation both in Europe and on the African continent. Rodney argued that it was precisely through exploiting existing class hierarchies in Africa that the European traders were able to construct the transatlantic system of slavery, which was so essential to the early history of capitalism. Rodney’s account thus cannot be dismissed on the grounds that it posits international trade as the determining factor of capitalist development to the exclusion of an analysis of class structure (see Brenner 1977: 88). Rodney’s method takes as its aim the integration of structures of production and structures of exchange.

The second contribution I highlight flows from this theoretical framework and concerns the question of unfree labor in the history of capitalism. In the tradition of Eric Williams before him and of Immanuel Wallerstein after him, Rodney’s work grasps that capitalist production on a world scale involves multiple forms of labor, including various gradations of free and forced labor (as with Banaji 2011). This comes through especially powerfully in his book on working-class formation in sugar plantation economy of British Guiana. There, Rodney does away with formalistic theories on both sides of the theoretical divide. Capitalism is constituted neither by wage labor relations alone nor by an industrial core defined by wage labor and a periphery defined by bonded labor. Instead, Rodney’s analysis of colonial capitalism in British Guiana captured complex dynamics of labor control spanning wage labor, slavey, and indenture, in addition to the struggles of independent subsistence labor. This represents an important advance in theorizing core-periphery relations in the global political economy.

Finally, Rodney offered a unique contribution to the theorization of race and racism in a capitalist system. Rodney dealt with the difficult questions of race and class in various ways and for different audiences throughout his career. But it would not seem inappropriate to give special weight to his most mature and developed work on colonial capitalism and class formation. That work contains a remarkable chapter called “Race as a Contradiction Among the Working People.” While acknowledging that workers of African and Indian origins had inherited distinct and competing interests from a long history of struggle, the chapter challenges the dominant scholarly view that the whole of Guyanese history had been marked by persistent racial conflict among workers. Rodney rejected this primarily on empirical grounds: scouring the archives, the evidence to support such a claim just wasn’t there. Rodney thus offered an alternative and more constructive interpretation: the Guyanese working class suffered not from the presence of inherent racial conflict, but from the absence of a mature working-class political culture.

Rodney dedicated the last part of his life to the struggle to construct such a culture. Characteristically, Rodney pointed out that it was the elite classes (including professional academics) who benefited far more than working people from the idea that racial groups possessed inherently conflicting interests. Tragically, it was precisely this sort of thinking that put a target on his back.

Building on Rodney

What does all this mean for contemporary approaches to political economy and development? First, it means that we need to let go of rigid frameworks that split our understanding of capitalism into domestic and international compartments. It is not only possible, but imperative, to ground our studies of class formation and international development in their mutual and overlapping dimensions. Second, we need a better understanding of how capitalism has employed, and continues to employ, variegated forms of labor control (LeBaron and Phillips 2019). Third, and on the practical side, returning to Rodney can help clarify certain deadlocks in contemporary political discourse, especially concerning race and class.

Consider the endless debate on whether class is the primary concern of politics to the exclusion of racial identities, or whether attention to race and empire means ‘decentering’ class. Rodney teaches us that both of these positions are equally disastrous – and really two sides of the same coin. To ‘decenter’ class would certainly be a non-starter from Rodney’s perspective. But to abstract class from the social identities that cohere within classes would be no less absurd and self-defeating.

Rodney’s approach to the political economy of development embodies the imperative of class analysis, which leads us necessarily to grappling with complex social identities in an international frame. Returning to Rodney can aid us in pressing forward on all these questions in the analysis of concrete conjunctures, whether historical or contemporary.

References

Antunes de Oliveira, F. and Kvangraven, I.H. (2023) ‘Back to Dakar: Decolonizing international political economy through dependency theory’, Review of International Political Economy, 30(5), pp. 1676–1700. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2169322.

Banaji, J. (2011) Theory as History: Essays on Modes of Production and Exploitation. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Brenner, R. (1977) ‘The Origins of Capitalist Development: a Critique of Neo-Smithian Marxism’, New Left Review, pp. 25–92.

Chilcote, R.H. and Salém Vasconcelos, J. (2022) ‘Introduction: Whither Development Theory?’, Latin American Perspectives, 49(1), pp. 4–17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X211070020.

Frank, A.G. (1969) Capitalism and underdevelopment in Latin America: historical studies of Chile and Brazil. New York: Modern Reader Paperbacks.

Jenkins, D. and Leroy, J. (eds) (2021) Histories of Racial Capitalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Johnson, D.K. (2023) ‘Walter Rodney and the method of political economy: retrieving a critical-historical IPE’, Review of International Political Economy, 30(2), pp. 421–436. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2153263.

Kvangraven, I.H. (2021) ‘Beyond the Stereotype: Restating the Relevance of the Dependency Research Programme’, Development and Change, 52(1), pp. 76–112. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12593.

LeBaron, G. and Phillips, N. (2019) ‘States and the Political Economy of Unfree Labour’, New Political Economy, 24(1), pp. 1–21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1420642.

Prashad, V. (2008) The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World. New York: The New Press.

Rodney, W. (1970) A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545-1800. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rodney, W. (1981) A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rodney, W. (2018) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Verso Books.

Wallerstein, I. (1974) The Modern World-System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press.

Wallerstein, I. (1986) ‘Walter Rodney: The Historian as Spokesman for Historical Forces’, American Ethnologist, 13(2), pp. 330–337.

Wood, E.M. (2002) The origin of capitalism: a longer view. London: Verso.

World Bank (2024) International Debt Report. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/42444.

David Kenneth Johnson is a Fellow in the Department of International Relations at the London School of Economics. His research examines the entwined histories of capitalism and empire, the political economy of US foreign policy, and international monetary hierarchy. His work has been published in Review of International Political Economy and Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of International Studies.

Photo: Walter Rodney Foundation.

Publisher: Source link