By Claudius Gräbner-Radkowitsch and Birte Strunk

The degrowth movement is a radical attempt to challenge our current economic system, arguing that its excessive focus on economic growth will ultimately harm people and planet. It has recently gained increasing attention, not only because it has found its way into mainstream political debates (see, for example, the Beyond Growth conference at the European Parliament), but also because related research projects have won prestigious international funding awards (see, for example, here). However, as you may have noticed, these events are mainly taking place in the Global North. The concept as such was also originally developed in the Global North. At the same time, the movement is strongly committed to the idea of global justice and a decolonization of relations between the Global North and South.

This begs the question: What is the role of the Global South in the contemporary degrowth discourse? To what extent does the discourse take into account Southern perspectives? Does it think that the South should also degrow, or is Northern degrowth mainly seen as a self-prescription? And to what extent does the degrowth community reflect on the implications of Northern degrowth for the Global South? To answer these questions, we have taken stock of how the academic degrowth discourse considers the Global South. But before we go into the details of what we found and what we make of it, let us briefly outline what degrowth is all about.

What degrowth is about

Degrowth is both an academic field of study and an activist movement. While it has gained traction largely because of the growing relevance of global climate crises, part of its origins lie in a field that historically had a different focus: namely in culturalist critiques of modernity, questioning Western narratives of progress, development and growth.

Given its internal heterogeneity, the field is not easy to characterize. Internal debates about the precise meaning of the term “degrowth” – see, for example, this paper on “What does degrowth mean?” and these two responses – do not make this task any easier. Nevertheless, we may be on the safe side if we define degrowth as a scholarly and activist movement that is highly critical of the alleged dependence of global capitalism on economic growth and that aims at a radical transformation towards a more socially just and ecologically sustainable world economy, primarily by breaking the growth dependency of the current system.

Degrowth scholars regularly and rightly point out that many intellectual inspirations and key concepts originated with thinkers from the Global South, but the concept of degrowth as such is a Northern invention of the late 2000s, most commonly associated, in its inception, with the French philosopher Serge Latouche and his subsequent followers. Despite its intellectual origin in the North, the current degrowth discourse understands itself as a global project, explicitly concerned with addressing global injustice. This perspective is evidenced not only by the regular lip service paid to the decolonization of the South, but also by the many references in the literature to post-development contributions. But how exactly do degrowth scholars take into account the Global South?

What role does the Global South play in the academic degrowth discourse? A topical focus on synergies

In a recent paper, we conducted a systematic (quantitative and qualitative) review of the academic degrowth literature on the Global South. We wanted to find out: How do degrowth scholars themselves think and write about the relation between degrowth and the South? We identified 52 key publications on the topic, published between 2009 and 2022. The vast majority of these were written by authors affiliated with institutions in the Global North (more information on the methodology used can be found in the article and the corresponding data material).

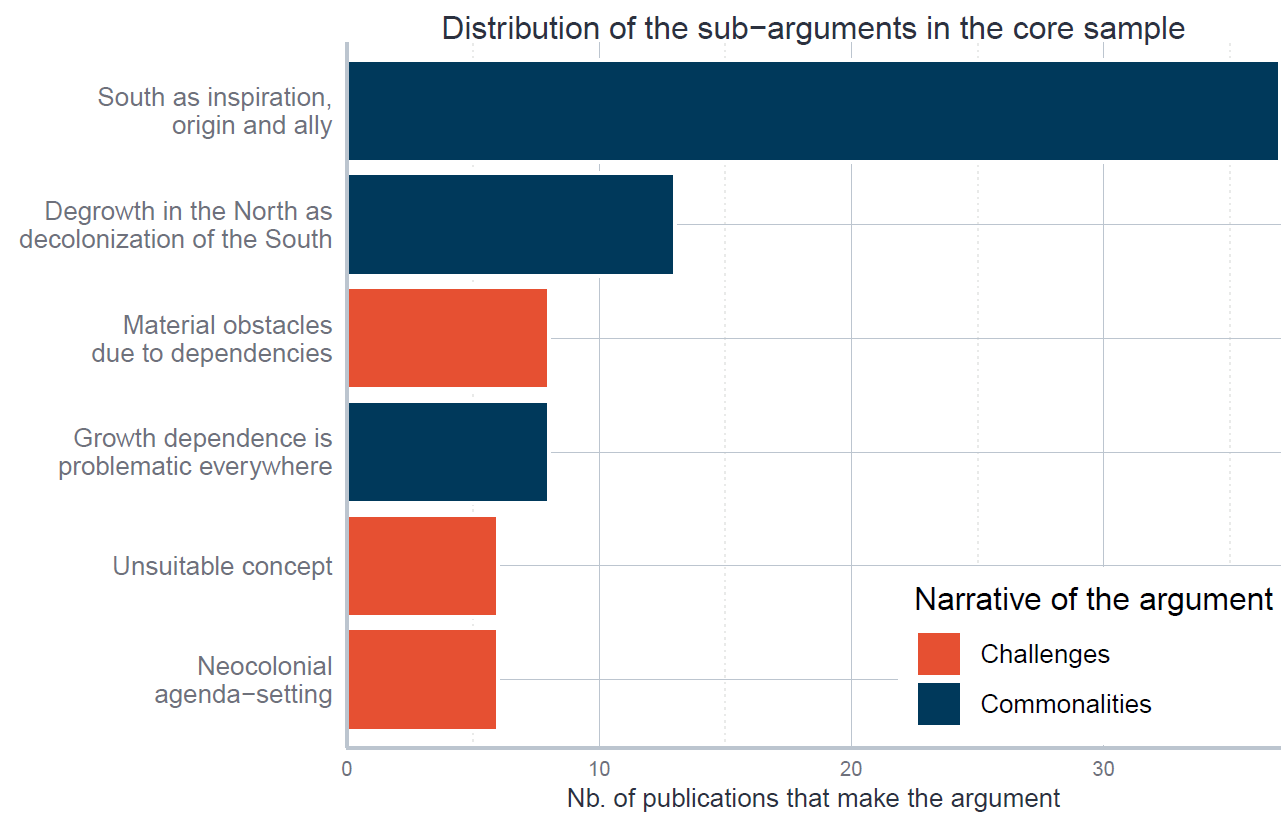

Analyzing these publications with respect to the question “How does degrowth relate to the Global South?” suggests the presence of two main narratives: one on synergies between degrowth and the South, and one on challenges. Publications following the synergies narrative emphasize the commonalities between Southern and Northern perspectives on degrowth. Papers following the challenges narrative remain mostly sympathetic to degrowth, but focus on challenges that emerge from thinking about degrowth and the Global South. Interestingly, more than two-thirds of the core papers follow the overall synergies narrative.

Going into further detail, we identified three sub-narratives for each of the two main narratives:

In practice, these sub-narratives were often mixed within single publications. For example, a paper classified following an overall challenges narrative might start with the observation that Southern movements and degrowth can be potential allies (i.e. a synergy argument), but that there is a danger of neocolonial agenda-setting that degrowth needs to deal with to a greater extent (see e.g. this or this paper).

Interestingly, more than two-thirds of the core papers follow the overall synergies narrative. Among these, the most common argument is that degrowth ideas originate in Southern thinking and can be inspired by Southern practices (see Figure 1). Postcolonial and post-development arguments are also regularly referred to, especially in the more recent papers, and the hope is expressed that if countries in the Global North were to implement degrowth policies, this would be an important step towards the decolonization of countries in the Global South.

This process of decolonizing the South through the implementation of degrowth policies in the North may be hindered, however, by structural dependencies between the South and the North, such as asymmetric trade relations, financial dependencies, or simply power hierarchies in the context of international organizations. This argument is the most frequent challenge mentioned in the current literature, yet we found more articles that raise this issue (e.g. here or here) than articles that discuss potential solutions to it (e.g. here).

The twin problem of structural dependencies

In fact, these structural interdependencies play a complex role in the degrowth literature: Within the current institutional framework, they are both a motivation for and a potential obstacle to degrowth. On the one hand, the current distribution of economic activities is often to the detriment of countries in the South. The global division of labor tends to exacerbate inequalities and facilitates the externalization of social and environmental costs to countries in the global South (see, for example, here). Indeed, for many degrowth scholars this grim state of affairs is one of the main reasons why they subscribe to the degrowth program in the first place.

On the other hand, however, there is a flip side to this story that lies at the heart of the “twin problem”: many people in the South are now dependent on the money flows that come from the North as payment for these products, just as they are often dependent on the provision of credit and remittances, the import of products and services for which countries in the South lack either the technological capacity or the patents, or access to currencies issued by countries in the global North.

These dependencies complicate the program of decolonizing the Global South by implementing degrowth in the Global North: attempting to eliminate unequal exchange relations by implementing degrowth in the North could, at least in the short term, create even greater calamities, at least without simultaneously addressing the structural problems at the global level. Thus, while degrowth scholars rightly argue that the existence of exploitative relationships to the detriment of the South should not be used as a fundamental argument against degrowth as such, the question of how exactly to overcome these dependencies in practice is an important one that degrowth scholars have not yet addressed sufficiently.

What is the right level to address the twin problem?

The twin problem relates to a rather fundamental question, not only for degrowth, but for all movements that aim to fundamentally change our socio-economic system: what is the appropriate political strategy to initiate the desired changes, and who are the relevant actors? Traditionally, degrowth shares with many initiatives from the post-development camp an appreciation of bottom-up and interstitial strategies, and a certain skepticism about top-down and state-centered approaches. And while the discourse on political strategy in the degrowth community as a whole has broadened, contributions around bottom-up resistance are currently much more elaborated than contributions around higher-level policy making, especially when it comes to the topic of “Degrowth and the Global South”. However, structural dependencies cannot be easily addressed – or even understood – with a sole focus on the local. In our article, we therefore suggest that degrowth scholars could benefit from taking a closer look at the contributions of other radical research programs, especially when it comes to the analytical understanding of the mechanisms underlying structural dependencies.

Inspirations on how to tackle the twin problem

The first contribution that comes to mind in this context is the work of the Marxist political economist Samir Amin on delinking (see also this blog post on Samir Amin’s continuing relevance), which is precisely about how Southern countries can become less dependent on global institutions and Northern countries. Delinking is not about autarky or deglobalization, but about strategies for Southern countries to become more autonomous and independent. This includes, but is not limited to, delineating their own development models (which may or may not include elements of Western development models), reorganizing their production systems, and building South-South cooperation that will allow them to become less dependent on global markets and financial flows (for more details, see, for example, this editorial).

Beyond the issue of delinking, there are a number of strategies for addressing structural dependencies that heterodox economists and critical development scholars have been working on, such as the substitution of North-South trade relations with South-South trade relations (e.g. here), technology transfer to the South combined with sophisticated infant industry protection (e.g, here), the immediate consideration of an unequal distribution of technological capabilities (e.g., here) and persistent historical dependencies (e.g., here), the critical assessment of financial hierarchies (e.g., here or here), or the implementation of “civilized trade institutions” on a global scale (e.g., here).

There is an important commonality in all these debates, and we believe that it is a commonality that degrowth scholars share with other radical scholars – even with those who might themselves be very skeptical of degrowth as such. Namely, the conviction that structures matter. Degrowth and other radical scholars might thus be united in their perspective that, in order to improve living conditions globally, institutional changes in both the North and the South are necessary. The network of global interdependencies makes unilateral change virtually impossible, and it is a great misfortune that the dominant paradigm in economics is particularly ill-suited to identify and critically discuss these structuralist dependencies (for more details see here).

Outlook

In all, we found a range of responses to the question that we asked in the beginning: How does degrowth, as a mainly Northern discourse, relate to the South? We showed that many degrowth contributions highlight the synergies between degrowth thinking and radical thought and action in the South. Moreover, degrowth in the North is often seen as a necessary step to decolonize economies in the Global South, since the current structures of growth-based global capitalism are largely beneficial to the North and detrimental to the South. Nonetheless, as some degrowth contributions have also started to point out: it is precisely because of these structures, that Northern degrowth might not have the desired effects of promoting global justice, at least in the short-term and at least not without radical institutional reforms of international systems of trade, finance, politics and law. How such radical institutional reforms might look like concretely, however, has not been discussed very concretely within the degrowth literature we reviewed. In our article, we thus bring together a range of topics and methodologies from other fields of heterodox economics or global studies, which might yield fruitful perspectives if included into a degrowth research program. Only then, we argue, can degrowth effectively address both sides of the twin problem of structural dependency.

Birte Strunk is a PhD candidate in economics at the New School in New York City. Having previously studied economics and philosophy in Maastricht, London, and Vienna, she currently pursues research at the intersection of ecological economics and labor economics, with a focus on inequality and work hours. As part of her PhD, she spent a semester as a visiting research fellow at Harvard University, and she also currently pursues a Masters in philosophy at Fernuniversität Hagen next to her PhD. She has published on feminist ecological economics, degrowth and philosophy of (plural) economics.

Claudius Gräbner-Radkowitsch is Assistant Professor of Pluralist Economics at the Europa-Universität Flensburg (Germany) and Research Associate at the Institute for the Comprehensive Analysis of the Economy (ICAE) of the Johannes Kepler University Linz (Austria). He holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Bremen and has worked on comparative development dynamics in the European Union, the socio-economic implications of green transformations, the determinants and implications of technological change and economic complexity, as well as on the sociological and philosophical foundations of pluralism in the social sciences, including the relation between pluralism and decoloniality. Claudius’ X handle is @ClaudiusGrabner

Photo: Mike Langridge.

Publisher: Source link