We provide new spatial and historical data to overturn the common claims that (i) African borders were decided at the 1884-85 Berlin Conference and that (ii) African borders are as-if random. Instead, African borders resulted from a decades-long competitive process among Europeans that Africans also influenced. Most borders follow and reflect geographic and political realities, in particular, water bodies and the historical frontiers of African states.

It Didn’t Happen at Berlin

Our recent article (Paine, Qiu and Ricart-Huguet, 2025) overturns two important pieces of conventional wisdom about border formation in Africa. First, the claim that borders in Africa were decided at the 1884–85 Berlin Conference. Second, the persistent idea that African borders are arbitrary with respect to the realities on the ground.

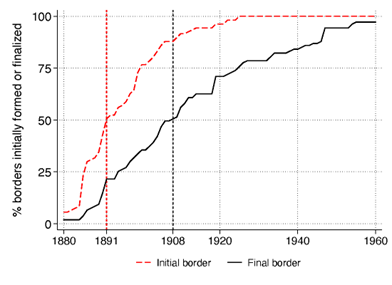

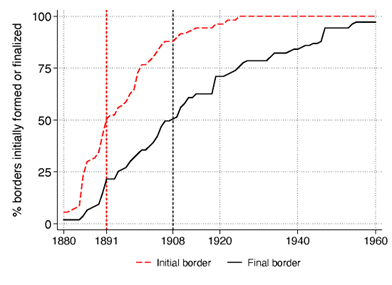

Historians of Africa have long rejected the idea that the Berlin Conference was a seminal event for the division of Africa, but its imagined importance remains a “stubborn myth” among non-specialists (Nugent 2019, 18) and a “cliché [that] has endured despite efforts of historians to destroy it” (Boilley 2019, 5). Indeed, we find that half of Africa’s international borders did not exist in any form until 1891, and half the borders were modified in major ways after 1908, more than two decades after the Conference concluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Timing of African border formation

Border Formation in Africa Was a Dynamic, Negotiated, and Protracted Process

Europeans indeed knew little about Africa in the 1880s, were self-interested, and had little regard for Africans. However, to make compelling territorial claims, Europeans had to learn facts about on-the-ground realities. This forms the basis of our alternative theoretical account, which emphasizes that border formation in Africa was a dynamic and protracted process grounded on local features—contrary to the second common claim that African borders are largely random.

One regularly accepted rule to minimize inter-European conflict was the principle of suzerainty: a power that signed a recognized treaty with an African ruler gained all the territory within that ruler’s domain. This drove Europeans to gather information and sign a flurry of new treaties with African chiefs following the Berlin Conference. The principle of suzerainty also encouraged the use of historical frontiers as guides for borders, as opposed to partitioning precolonial states. Both European imperial agents and African leaders had incentives to overclaim. This produced a competitive process whereby Europeans renegotiated borders over time as they gathered information to support their territorial claims.

For example, the original 1890 division between British and French territories in today’s northwestern Nigeria was an arbitrary straight line. Via a competitive process influenced by the locations of Yoruba states and the Sokoto Caliphate, the powers redrew the border in 1898 and again in 1904, as visually shown above. Rivers and lakes were also objects of negotiation because of their value for trade and transportation. The borders throughout the Great Lakes region are inexplicable without reference to its lakes, many of which were also the frontiers of precolonial states (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Great Lakes and borders in East Africa

Determinants of African Borders: A Quantitative Test Using Grid Cells

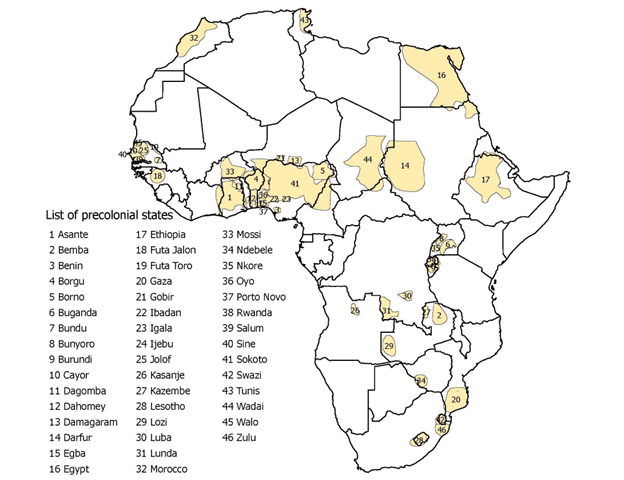

We perform two systematic empirical exercises to test our theory. We first examine the determinants of border location using 0.5° × 0.5° grid cells. Our outcome variable is whether a cell contains a border segment, and our explanatory variables identify cells with local characteristics, mainly rivers, lakes, and precolonial states. We combine numerous historical sources and atlases to compile a list of precolonial states in the mid-19th century, prior to European imperial expansion (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Precolonial states and contemporary borders

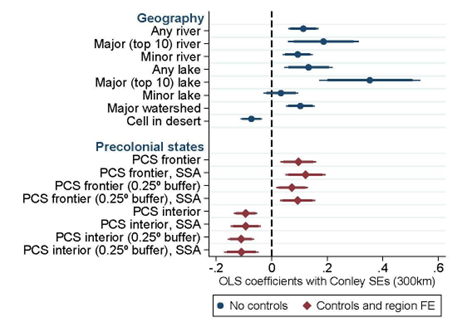

Rivers, lakes, and the frontier zones of precolonial states correlate positively with the location of contemporary borders, whereas the interior areas of precolonial states correlate negatively (see Figure 4). The results support our claim that European powers used the frontiers of precolonial states but rarely partitioned them.

Figure 4. Regression estimates

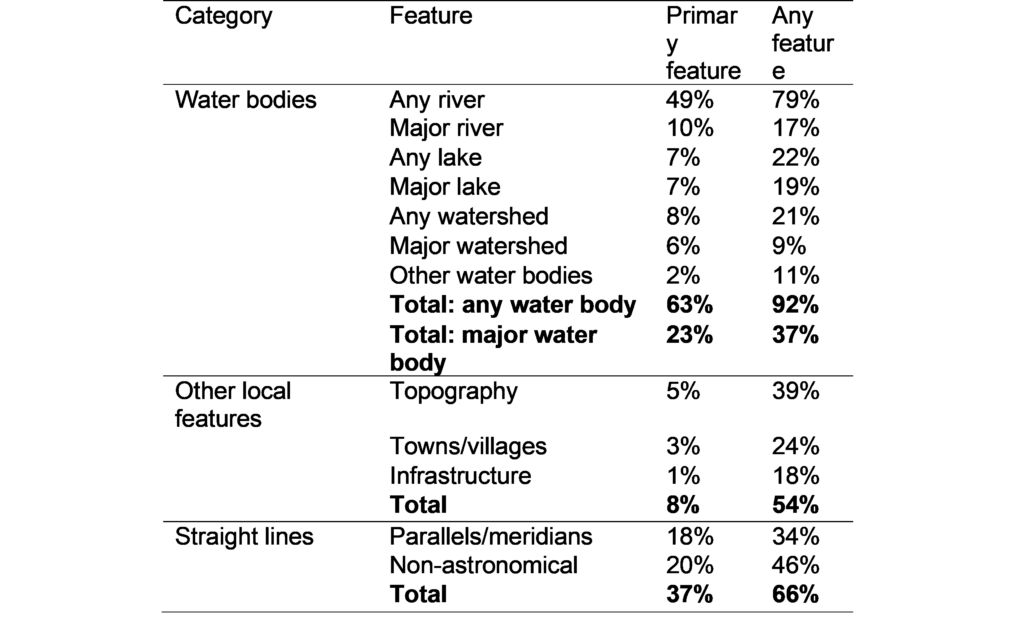

A Historical Examination of All Borders

We also examined the history of all 107 bilateral borders, yielding three findings. First, borders were finalized much later than commonly assumed (see Figure 1). Second, Europeans settled 62% of bilateral borders in accordance with the location of African precolonial states, non-European states (e.g., the Ottoman Empire), earlier white settlements, or (more rarely) migration zones of nomadic groups. Third, the typical border is determined by about 3.5 features, often water bodies but also other features such as mountains and towns (see Table 1). By contrast, straight-line borders are less prevalent than often claimed and are concentrated in remote, sparsely populated areas like the Sahara Desert.

Table 1. Features of African Bilateral Borders

Conclusion

Our work contributes to a growing literature—led by political scientists but relevant across the social sciences—highlighting the shortcomings of treating borders as natural experiments in Africa (McCauley and Posner, 2015) and beyond (Dunning, 2012; Kocher and Monteiro, 2016). The division of peoples may be as-if random in some cases, such as the since-eliminated border between Southern British Cameroons and French Cameroon (Lee and Schultz 2012, Dupraz 2019) or the straight border between Kenya and Tanzania. However, we cannot assume that borders are located arbitrarily in general, or even that all straight-line borders are—some straight-line borders in the Sahara reflect the homelands of different Tuareg subgroups (Boilley 2019). Although many colonial states in Africa were largely artificial, in the sense that they did not exist prior to colonization, the borders between them were not.

References

Paine, J., Qiu, X., & Ricart-Huguet, J. (2025). Endogenous Colonial Borders: Precolonial States and Geography in the Partition of Africa. American Political Science Review, 119(1), 1–20.

Boilley, P. (2019). Nord-Mali: les frontières coloniales de l’Azawad. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 53(3), 469–484.

Dunning, T. (2012). Natural Experiments in the Social Sciences. A Design-Based Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Dupraz, Y. (2019). French and British Colonial Legacies in Education: Evidence from the Partition of Cameroon. Journal of Economic History, 79(3), 628–668.

Kocher, M. A., & Monteiro, N. P. (2016). Lines of Demarcation: Causation, Design-Based Inference, and Historical Research. Perspectives on Politics, 14(4), 952–975.

Lee, A., & Schultz, K. A. (2012). Comparing British and French Colonial Legacies: A Discontinuity Analysis of Cameroon. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 7(4), 365–410.

McCauley, J. F., & Posner, D. N. (2015). African Borders as Sources of Natural Experiments. Promise and Pitfalls. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(2), 409–418.

Nugent P. Boundaries, Communities and State-Making in West Africa: The Centrality of the Margins. Cambridge University Press; 2019.

Feature Image: Nigeria’s Northwestern Borders (Source: Paine et al. (2025)).

Publisher: Source link