Deindustrialization theories have long purported that industrial production in sub-Saharan Africa and most other parts of the Global South fell into rapid decline by the nineteenth century due to rising competition – and often coercion – by industrializing nations in the Global North. In contrast, we find that domestic textile manufacturers across sub-Saharan Africa and Java wielded certain advantages during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which allowed them to compete and even flourish amid globalization and colonization. Chief among these was their ability to cater to complex and diverse local consumer tastes.

For decades, the link between manufacturing, economic development, and colonialism during the globalizing nineteenth and twentieth centuries has been subject to considerable debate. Dependency-school theorists have long argued that imperial ‘core’ countries stifled domestic handicraft industries in the ‘periphery’ by flooding colonial markets with low-cost manufactures from the metropole while coercing colonized people to channel their labour into the production of raw materials (Frank 1966; Rodney 1972). More recently, neoclassical economists have contended that industrial development was inherently handicapped in much of the Global South by, for example, geographic conditions that predisposed tropical regions to export-oriented primary production in lieu of manufacturing (Williamson 2011). Both schools share certain key assumptions: first, that the Western model of modernization was the exclusive road to development; second, that handicraft industries in the Global South were unable to withstand competition from machine-made imports; and third, that the ability of colonized regions to achieve economic growth was principally determined by demand and/or policies from the Global North.

Rethinking Deindustrialization

In recent decades, scholars have increasingly refuted the notion of a straightforward ‘deindustrialization’ in the Global South. This revised perspective rests in part on a reframing of the concept of deindustrialization. While dependency and neoclassical scholars have narrowly cast deindustrialization as a relative decline in the output of industry compared to other economic sectors, case studies have highlighted industrial resilience and even expansion – in terms of nominal output, labour force participation and innovation – in what has formerly been identified as ‘deindustrialized’ regions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, Indonesia and India (e.g., Frederick 2020; van Nederveen Meerkerk 2017; Roy 1993). Such studies reveal that small-scale artisans often survived and even prospered by utilizing labour- and skill-intensive methods to cater to domestic markets.

In our recent article in the Journal of Global History, we push beyond region-specific case studies to develop a comparative South-South perspective with the aim of uncovering how local industries coped with the effects of globalization under colonial rule. We combine our expertise on the history of domestic cloth production across sub-Saharan Africa and Java to identify certain key advantages that enabled domestic producers to remain competitive. These included their ability to cater to highly specified local demand preferences, their flexible access to both local and global industrial inputs, and the (seasonally) low cost of industrial labour in much of the Global South.

The Power of Preference

The ability of many African and Javanese handicraft textile producers to persevere and even flourish in the context of globalization was strongly linked to the capacity of local producers to cater more effectively and efficiently to certain segments of the consumer market than most suppliers of mass-produced imports. Not only were nineteenth- and early twentieth-century hand-woven products often higher in quality than mass-produced factory-made imports due to a greater focus on craftsmanship, they were also precisely geared toward differentiated consumer preferences. This constituted an important advantage afforded by both the closeness – in physical and cultural terms – of domestic producers to their consumer base and the greater flexibility of small-scale producers to quickly alter their designs and methods to accommodate specific – and changeable – consumer demands.

Rather than buckling under the pressure of competition, many local handicraft artisans operated parallel to rising machine-produced imports: from Wafipa weavers in what is today southwestern Tanzania, who deftly accommodated consumer requests based on ‘taste, vanity or rank’ and altered prices accordingly (Wyckaert 1927, p. 368); to Akwete weavers in Nigeria, who could produce a vast range of intricate designs in response to shifting demand patterns; to Kente cloth weavers in Ghana, whose characteristic checkered designs (Figure 1) continued to find ready markets next to European imports of factory-made imitation wax prints. Meanwhile, we find that a majority of the cloth imported into Africa and Java consisted of plain, often monochromatic fabric well into the twentieth century. Consequently, even where local industries experienced a decline in the domestic market share, which indeed occurred across the Global South, this did not necessarily imply broad deindustrialization since local products continued to fulfil particular local consumer demands that imports were ill-equipped to satisfy.

Figure 1: Kente cloth from the Gold Coast, late-nineteenth to early-twentieth century

Source: Brooklyn Museum, Robert B. Woodward Memorial Fund, 71.211.

Local Benefits of Global Trade

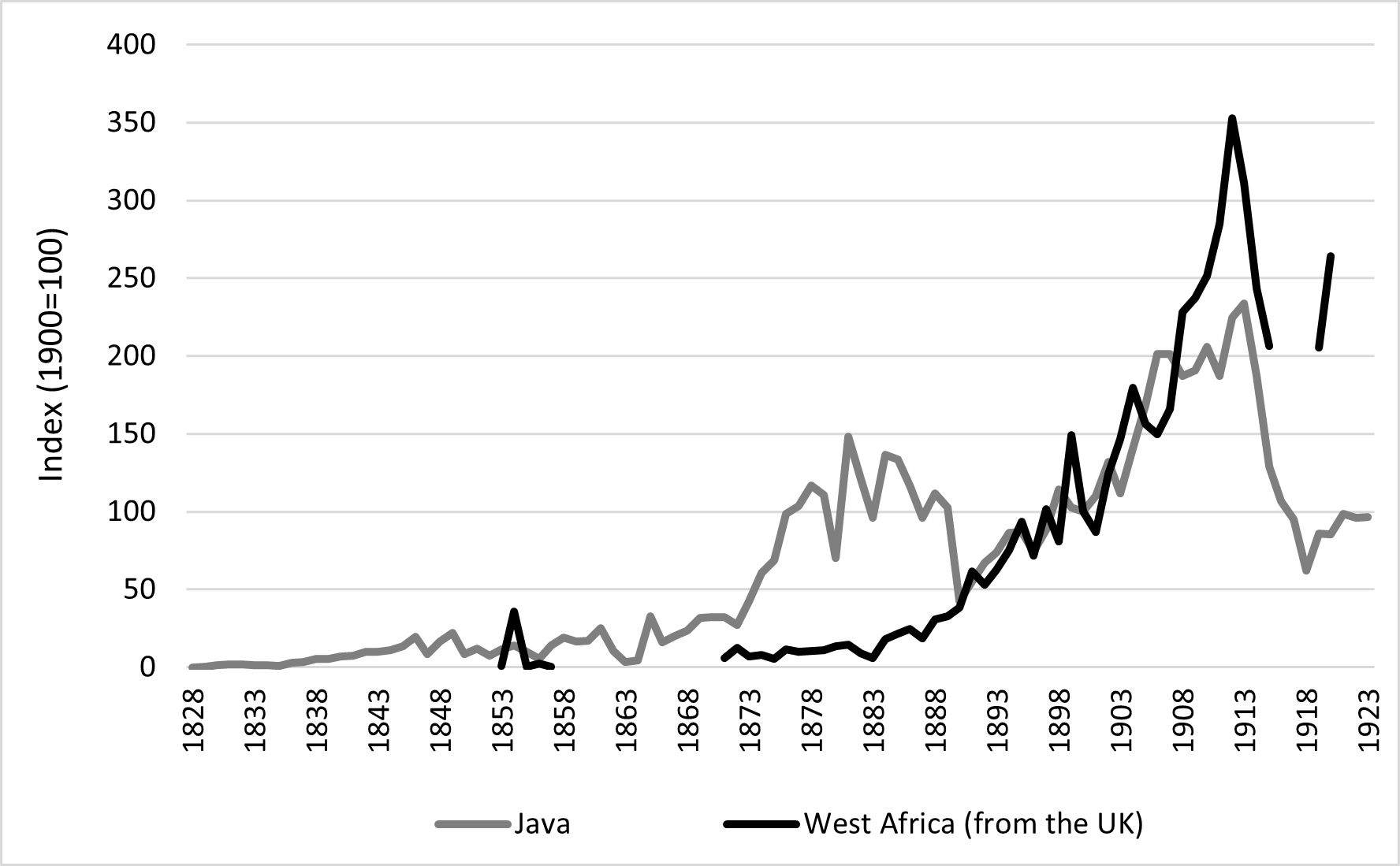

Moreover, we find that local industries often benefited from global trade integration. The often-assumed zero-sum relationship between handicraft and machine-based manufacturing obscures what in some cases could be complementary dynamics. In Java, for example, batik cloth producers often used unbleached cloth to produce low-cost handprinted garments geared to lower-end consumers. Similar printing techniques likewise emerged in East Africa. In both sub-Saharan Africa and Java, imports of machine-produced yarn boomed during precisely the period of industrial demise typically highlighted in deindustrialization literature (Figure 2). Rather than precipitating a disappearance of local manufacturing, unfinished imports bolstered local weaving, in many cases controverting the expectations and hopes of colonial officials who viewed the colonies principally as sources of raw materials and markets for metropolitan imports.

Figure 2: Index of yarn imports into Java and West Africa, 1828-1923

At the same time, the particularities of labour dynamics in much of the Global South helped artisanal weavers remain competitive with machine-made imports, even in terms of price. Most artisans were self-employed weavers who operated part-time as subsistence farmers and could thus supply their alimentary needs regardless of income. This meant that their cost of living was not passed on to their consumers in the form of elevated cloth prices. Some weaver-farmers also grew cotton to produce their own yarns, thus enjoying access to both local and global yarn supplies. Adaptation and flexibility in terms of both materials and labour inputs thus provided an additional layer of security as artisans competed with manufactures from the Global North.

Conclusion

Taken together, highly attuned responses to consumer demand, access to global markets for industrial inputs, and seasonally low industrial labour costs helped handicraft producers across sub-Saharan Africa, Java, and likely much more of the Global South thrive amid globalization. The capacity of producers to adapt to changing market conditions was indicative of the considerable degree of agency exercised by both domestic producers and consumers amid increasing colonial interventions that often aimed at diverting raw materials to metropolitan industrialists and funnelling metropolitan manufactures into colonial markets.

References

Frank, A.G., (1966) The development of underdevelopment. Monthly Review, 18(4), 17-31.

Frederick, K. (2020). Twilight of an industry in East Africa: Global trade, colonial rule, and textile manufacturing, 1830-1940. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Frederick. K. & van Nederveen Meerkerk, E. (2023). Local advantage in a global context. Competition, adaptation and resilience in textile manufacturing in the ‘periphery’, 1860–1960. Journal of Global History, 18(1), 1-24.

Van Nederveen Meerkerk, E. (2017). Challenging the de-Industrialization thesis: Gender and indigenous textile production in Java under Dutch colonial rule, C. 1830–1920. Economic History Review, 70(4), 1219–1243.

Rodney, W. (1972). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Redhill: Love and Malcomson.

Roy, T. (1993). Artisans and industrialization: Indian weaving in the twentieth century. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, J.G. (2011). Trade and poverty: When the Third World fell behind. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wyckaert, R.P. Fileurs Et Tisserands. Les Missions Catholiques, 3031: 355-356, 367-368, 370.

Featured image: Brother Rodriguez. 1908-1909. “Die Baumwollkultur in Deutsch-Ostafrika.” Afrika-Bote: Nachrichten aus den Missionen der Weissen Väter 15: 223-227.

Publisher: Source link