Rosa, a 44-year-old woman who lives in Bogotá, has a problem when it comes to getting her 9-year-old girl, Alicia[1], vaccinated with the hugely effective Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine. She’s heard of the vaccine, but she hasn’t gotten it for Alicia because her pediatrician has not yet mentioned it in any of the girl’s check-ups and she’s not sure what the government’s attitude toward it is.

This puts Alicia at risk. HPV is one of the most common reproductive tract infections and can lead to a variety of cancers, in particular cervical cancer, a significant cause of death among women in Latin America, where the prevalence of HPV is the second highest after Sub-Saharan Africa. The World Health Organization estimates that 16.1% of women in Latin America have HPV compared to a worldwide average of 11.7%.

Experts agree that the best way to prevent HPV and cervical cancer is to vaccinate young people before they begin sexual activity. Yet, the region’s HPV vaccine coverage remains well below the levels seen in North America. Unfortunately for Alicia, and other girls like her, misinformation plays a role.

HPV Vaccination in Colombia

The situation in Colombia, where the government did an excellent job in offering the vaccine, offers an illustration of this predicament. Colombia was among the first countries in South America to implement the HPV vaccination and had one of the highest rates of coverage in Latin America. However, vaccination rates plunged when a group of young women in a coastal municipality suffered numerous side effects, including fainting spells, tachycardia, and chest pain, following their vaccination in an 2014 incident that received widespread media and social media coverage. A rigorous study by the Colombian National Health Institute found the outbreak of side effects to be of psychological, rather than physical origin. But the damage was done. Vaccination rates for the first dose of the vaccination regimen fell from over 97% in 2012 to 14% in 2016 and, after a resurgence, climbed again to around 39% in 2021 making the country only an average performer in the region.

The Health Ministry in Colombia supports the HPV vaccine and has made it free for girls between 9 and 17 years of age. Yet, in several interviews conducted during 2021, we found out that other parents in Bogota still shared Rosa’s uncertainty about doctors’ and the government’s opinion of it.

A Behavioral Economics Toolkit for Better Vaccination

This is where behavioral economics comes in. Using behavioral economics principles, we at the IDB have designed a toolkit for government officials facing similar challenges to those in Colombia to improve governments’ efforts in promoting the preventative measure. The toolkit, which is ready to download, walks practitioners and policymakers through an intervention conducted in Bogota to increase HPV vaccination using SMS messages.

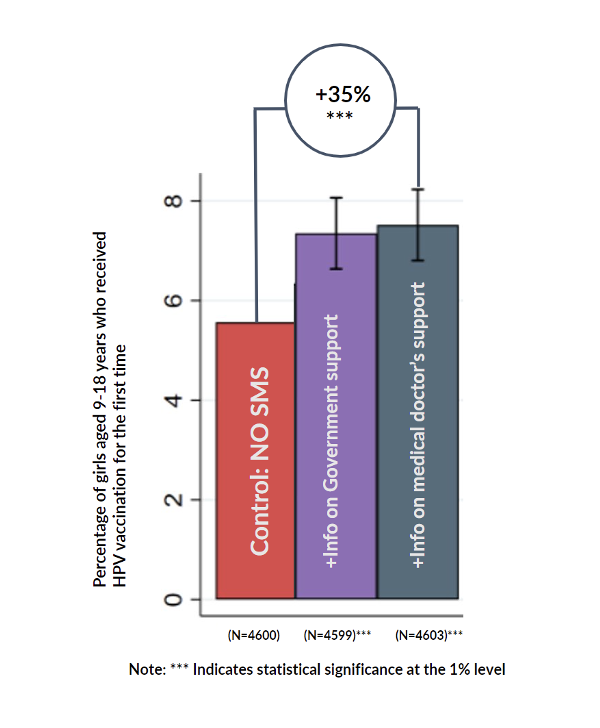

Some of the messages that were successful were designed with parents like Rosa in mind: messages indicating the government’s and doctors’ support for the vaccine. The group of mothers who received a message indicating doctors’ approval, for example, experienced a 35% increase compared to a control group that didn’t receive any message (see graph). The results from this and other messages tested in the intervention can be found on the IDB’s Behavioral Economics Group website. The toolkit explains the methodology applied, the results, and the content that proved most helpful. Most importantly, it is a guide for policymakers to help them think about ways to increase HPV vaccinations in their area.

The Importance of New Technologies

The work also points, among other things, to how the growing availability of mobile phones and the internet allows researchers to access people directly and cheaply. SMS messages, in particular, have increasingly been used to boost vaccination rates. For example, an experiment in Guatemala showed that SMS reminders to parents about their upcoming children’s vaccination date raised vaccination rates by 4.9 percentage points. This and other examples of the use of behavioral economics for improving health outcomes can be found in a recent publication by IDB’s Behavioral Economics group: Nudging Latin America and the Caribbean: A Decade of Improving Public Policies through Behavioral Economics.

The work on HPV vaccinations and the toolkit was a joint project with the American Cancer Society, the Behavioral Government Lab at the Universidad del Rosario, the Health Secretariat in Bogotá, and the Colombian Ministry of Health. Involving stakeholders ensures a better diagnostic, an implementation with fewer hiccups, and increases how much public officials learn and internalize. Strengthening the ability of policymakers to implement their own interventions is also part of the work we do.

Recent advancements have enabled researchers to leverage new technologies to improve vaccination rates in Latin America. That is great news for Rosa and millions of other parents who could, as a result, see significantly better health outcomes for their children in the decades to come. Policymakers should take note and promote these new tools, as they are cost-effective and can reach large shares of the population with substantial results.

[1] These names were changed to preserve confidentiality.

Publisher: Source link