The COVID-19 pandemic is dramatically affecting the lives of hundreds of millions of people in Latin America and the Caribbean, taking lives and exacting an immense toll on individual and national economies. Governments have responded with urgent assistance. But with a more than 10% decline in revenues as a result of closed businesses and lost jobs, governments now have to buy and distribute vaccines and spur their economies recovery with dwindling public finances.

These revenue shortfalls have serious implications. But the problem is not new. In most countries of the region, tax evasion and tax delinquencies are historically high. That is, many people don’t declare their business transactions or incomes, and even when they do, they often fail to follow through and pay their obligations. A few years ago, for example, tax delinquencies in Colombia amounted to more than US$2.5 billion, or about 20% of the country’s total tax evasion.

Employing Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics can help. It can identify creative and effective ways and technologies to encourage people to pay their taxes, one of many uses of behavioral insights with which the IDB has been experimenting in recent years.

Traditionally, most governments in the region use letters to contact delinquent taxpayers. In several projects conducted by the IDB with local government authorities, the content of those letters was modified to significantly improve tax receipts. For example, in one case we explained how the seemingly small interest rate on the penalty for property taxes could dramatically accumulate if left unpaid. This clearer messaging on the cost of non-compliance for taxpayers drove a 10% increase in tax revenues from the property tax and boosted collection of other taxes as well.

Boosting Tax Payments in Colombia

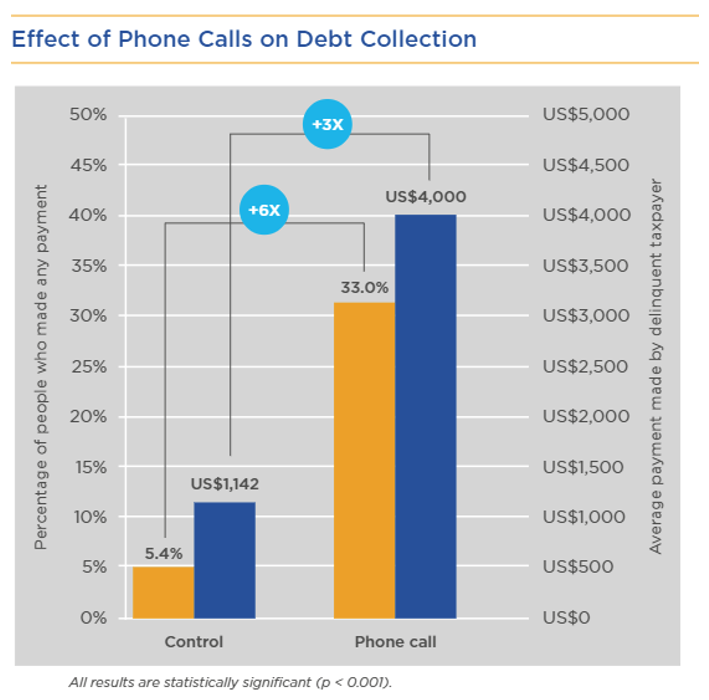

Other methods may be more effective still. In a recent study conducted by Mónica Mogollón, Daniel Ortega and I, we linked up with the National Tax Agency of Colombia (DIAN) to show that delinquent taxpayers targeted with phone calls were about 25 percentage points likelier to pay their taxes than a control group.

In the experiment, DIAN representatives randomly called taxpayers who had declared but not paid their taxes from a sample of 34,783 taxpayers with tax liabilities due. The DIAN representatives followed a detailed script that highlighted the consequences of non-compliance and included a message on the morality of fulfilling one’s tax duties: “Colombia, a commitment we can’t evade.” During the call, they either scheduled an appointment with the taxpayer at their local office or accepted a promise for payment.

Almost all targeted taxpayers agreed to meet with the agent at the local office as a result of the calls. But while only 50% of those who committed to pay actually did, the phone calls were highly cost effective: For every contacted taxpayer, the tax agency recovered almost US$4,000 in debt.

The results, however, varied across several taxpayer characteristics. To start with, the lower the level of debt, the higher the probability of payment was, a finding that suggests that tax authorities should contact taxpayers early, rather than let the debts persist and grow over time. Phone calls also seemed to be less effective for firms than for individuals; and people who owed valued-added (VAT) and income taxes reacted and complied more readily than those who owed wealth taxes. Finally, there is some evidence that phone calls can negatively affect chronic debtors — individuals with an outstanding debt of more than seven years.

All this illustrates that the communication technology governments choose for tax enforcement is not trivial: Different methods of communication signal different levels of enforcement capacity to taxpayers, and they inevitably have limitations.

Mixing Calls with Personal Visits as a Tax Strategy

If databases are not up to date for phone call campaigns, for example, the contact rate could be low. Second, chronic debtors may find ways to avoid being contacted as technology progresses. Third, as mentioned, phone calls may be less effective with certain delinquent taxpayers, like firms. So, the best strategy may well be a combination of cost-effective interventions, with limited phone calls targeting one group and personal visits, with the threat of more severe prosecution, targeting the small group of chronic debtors.

Also important are commitments and planning strategies, which in the case of this program meant asking taxpayers at each step of the process to commit to a next step and set a date for complying. These strategies seemed to work, but they were not foolproof, as promises outstripped follow-up. Tax compliance, of course, is easier said than done, and some of these failures may reflect social desirability bias — essentially the desire to please — in the taxpayer’s interaction with the tax agent, as well as procrastination in tax payment. This suggests that tax agencies should take full advantage of the effect of the personal interactions and make it easy for taxpayers to immediately follow through with their promises. Improving tax compliance is but one of many ways we at the IDB leverage behavioral insights across projects, in policy design, and in dialogue with different stakeholders. We also use them to improve educational outcomes, increase personal savings, and boost public health, among many other endeavors. But at this moment, when government revenue is low and the need for government spending is very high, we hope that these insights will encourage tax compliance and help governments get the revenue they badly need to fight the health and economic consequences of an unparalleled global crisis.

Publisher: Source link