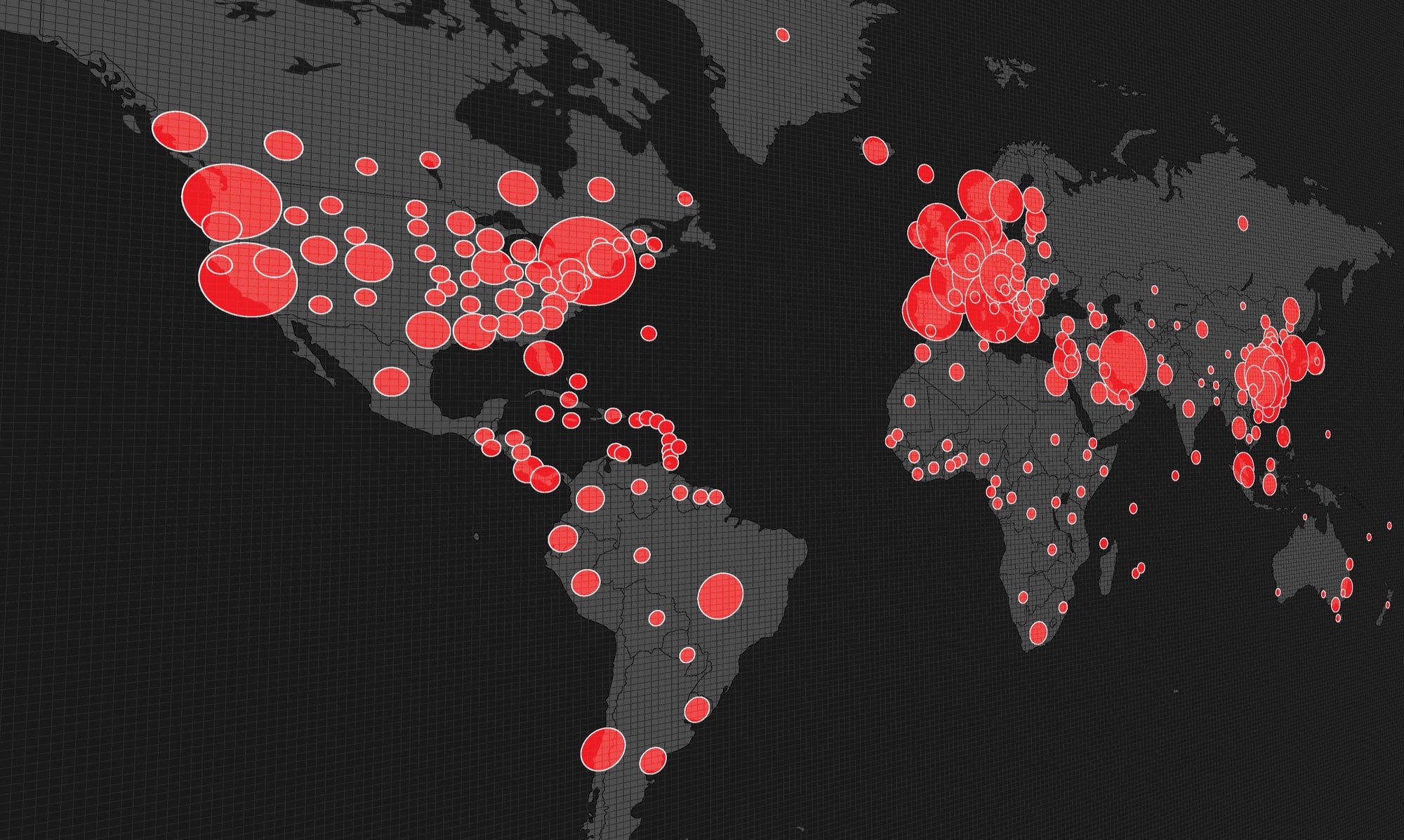

The pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) continues to severely impact countries around the world. More than 4.5 million people have been confirmed infected, and the death count is now in the hundreds of thousands, although stringent restrictions on mobility have prevented a greater public health disaster. However, economic stagnation and fatigue among the population have led many countries to decide to open their economies and ease restrictions on movement, even as the virus is still circulating widely. According to the Human Mobility Map for Latin America and the Caribbean, declines in mobility are slightly reverting. For instance, in Chile’s Santiago metropolitan area, mobility has increased by about 10 percentage points. Likewise for Cundinamarca (Colombia) and Lima (Peru).

In order for people to be able to move about without leading to a significant increase of cases, it is crucial for everyone to follow the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), which include maintaining physical distancing, washing hands regularly, and wearing facemasks. The good news is that, to promote hygiene practices and physical distancing in shared spaces such as factories and public transportation, behavioral economics can be of great help by offering recommendations to diagnose and design communications and interventions to counteract people’s cognitive biases. This will help keep the infection curve below levels that could collapse our healthcare systems.

To better understand how these behavioral tools can be used, we recently talked with Prof. Cass Sunstein, the co-author of Nudge and a professor at Harvard University. The talk was hosted by IDB President Luis Alberto Moreno, and here we summarize its main lessons.

FEAST: Designing Effective Messages for Latin America

In order to be effective, communication campaigns should follow the EAST framework designed by the Behavioral Insights Team (BIT). This framework emphasizes the importance of the following elements: (i) Easy – the messages and nudges have to be simple; (ii) Attractive – the messages should catch the attention of the recipient; (iii) Social – they must emphasize existing social norms that promote the desired behavior; and (iv) Timely – messages need to be presented in a timely manner, ideally when individuals are most susceptible to changing their behavior.

In the context of the current pandemic, where people are both anxious and fatigued, it is important to add a fifth letter to this framework, especially for Latin America and the Caribbean: F, for Fun, making the acronym “FEAST.” Messages or small changes that can add an element of fun to the daily routine can contribute to making measures like physical distancing more sustainable over time. An example of this new element is what New Zealand’s government did during Easter, introducing a fun element to the government’s narrative by declaring the Easter Bunny an “essential worker” and urging families to continue celebrating the holiday at home. “Fun theory” has been applied to a diverse set of behavioral interventions, as shown in this video. Nonetheless, it is important to note that one of the biggest challenges of these strategies is maintaining high levels of fun and surprise over time, which is key for sustainable behavioral change.

Is Fear an Effective Way to Encourage Compliance?

During an unprecedented crisis like this one, fear is a common denominator in our lives. But how effective is inducing fear at encouraging compliance with guidelines such as physical distancing? The effects could be either positive or negative depending on the approach of the strategy. Inducing fear with arbitrary bans can lead to a negative effect, as individuals might perceive the prohibition as a loss of control, and, considering that human beings are loss-averse, they might decide not to comply with the guideline or question its credibility.

On the other hand, emphasizing the risks of certain behaviors—such as an increased spread of the virus if physical distancing is not followed—along with clear directions to mitigate it, becomes a more effective strategy, in which fear is used to highlight a recommendation and not to impose rules. To further strengthen this effect, including components of hope can also be important. Thus, messages should communicate that complying with the guideline is an effective way to solve the problem, while also providing credible evidence for this statement.

Additionally, individuals tend to be overly optimistic, underestimating the probability of becoming infected. This means that they are more likely to change their behavior when the message is focused on the risk of infecting others and not on their own risk. Thus, messages that are focused on how individual actions can help achieve the common goal of reducing the spread of the virus are more effective, as shown in this recent study. Also, in this report produced by the IDB’s Behavioral Economics Group, we go into more detail on similar behavioral strategies to promote prosocial behavior, with the aim of containing and mitigating the consequences of the pandemic.

A Note on Optimism

Looking into the future with optimism has become a challenging task, especially considering how present bias has been enhanced by the high uncertainty levels that the pandemic has brought into our lives. Thus, Sunstein concluded our conversation by quoting Amos Tversky, a behavioral science pioneer: “When you are a pessimist and the bad thing happens, you live it twice: Once when you worry about it, and the second time when it happens.” Following Tversky’s statement, being an optimist becomes a rational choice during times of great global uncertainty. Remembering these words can serve as motivation to make the behavioral changes we must with optimism, recalling that the key to surviving and overcoming this crisis is collective action that requires the same of all of us.

Here is the full conversation with Professor Sunstein.

Publisher: Source link