What roles did Indians immigrants play in the economic history of sub-Saharan Africa’s first independent nation? From 1951-1966, Sindhi businessmen engaged with Kwame Nkrumah’s industrialization agenda for Ghana and established various manufacturing companies that constituted one aspect of the nation’s local industry. The extent to which they were involved in retail and wholesale trade from the 1930s and industry from the late 1950s shows that they were more than commercial intermediaries in Ghana’s economic history.

Indians and African Economic History

Literature on the economic history of West Africa has privileged European, and especially British, multinational companies who conducted different types of trade in goods and raw materials in the colonies through the 19th and 20th centuries (Fieldhouse, 1994; Decker 2023). These narratives mention, in passing, Indian and Lebanese trade intermediaries in the colonial economic arrangements without actually showing what roles they occupied and the extent of these roles. It also goes without saying that most scholarship on Indians in African history focus on Eastern and Southern Africa. While this scholarship discuss their economic contributions, they are predominantly driven by questions of race, belonging, and citizenship (Brennan 2012). By contrast, Indians in West Africa have remained obscure, even though a numerically small group of the Sindhi diaspora migrated to British colony of Gold Coast from the late 1890s and emerged as an economically influential group by the middle of the 20th century (Falzon 2004). In a recent paper (Mensah, 2023), I address this research gap.

Sindhis in Pre-1950s Ghana

Sindhis arrived in the Gold Coast from the late 19th century as petty traders, retailers, and wholesalers in Sindhi-branded firms such as Bombay Bazaar and Metharam Bros., located in the principal commercial towns of the colony. They sold household goods and fabrics mainly imported from Japan. The proximity of Sindhi shops to European ones in the business districts as well as their perceived whiteness by Gold Coasters made them targets in the 1948 riots, the first of a series of uprisings leading up to independence in 1957. Some Sindhi firms never recovered from the loss of revenue and goods. The few who survived transitioned into local industrial production to become small scale manufacturers, primarily in the garment industry.

Sindhis Factories and Local Industry from the 1950s

At the time of Ghana’s independence in 1957, one of Nkrumah’s economic goals was to rapidly industrialize the country in order to reverse the colonial economic policies which had turned Ghanaians into consumers, instead of producers of manufactured goods. Sindhi businessmen engaged with Nkrumah’s rhetoric for economic development through the self-financing of industries that produced different pieces of clothing, mosquito coils, umbrellas, sunglasses, and suitcases. These companies, listed in Figure 1, were located in a specially-marked industrial area, a few kilometres from the central business district. Although the factories were funded with initial capital from their previous retailing businesses, Sindhi manufacturers consistently tapped into state-sponsored initiatives such as tax relief, import duty exemptions, applications for pioneer company status, and loans to sustain and expand their industrial activities. In these applications, most of which were successful, they evoked the language of industrialization and the benefits the nation stood to gain from their activities.

Table 1: List of Sindhi Industries in Ghana by the late 1960s.

| Glamour Garment Factory | Loyalty Garment Industry |

| Intra-Knitting Works Ghana Ltd | Nagib Garment Factory |

| Esdee Manufacturing Company | Multi Garment Industries |

| Khemco Garment Factory | Utams and Nank Industry |

| Metropolitan Industries | Ashanti Shoe Factory |

| Mayfair Garment Industries | Ghana Candle Company Ltd |

| Ashanti Shoe Factory | Ghana Blanket Factory |

| Modern Jewelry & Industries | Ghana Incense & Perfumery Ltd |

| Ghana Umbrella Company | Ashanti Furniture Company |

| Ghana Mirror Factory | Novelty Garment Factory |

| Peekay Industries | Gokals Industries |

| Chanrai Industries Ltd | H.B & Sons Industries Ltd. |

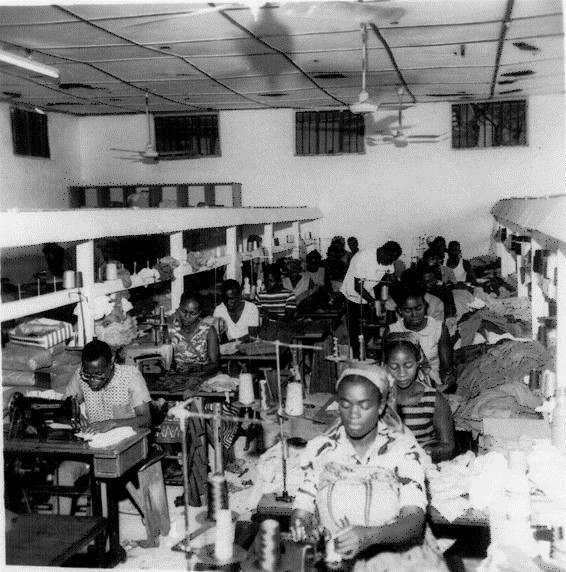

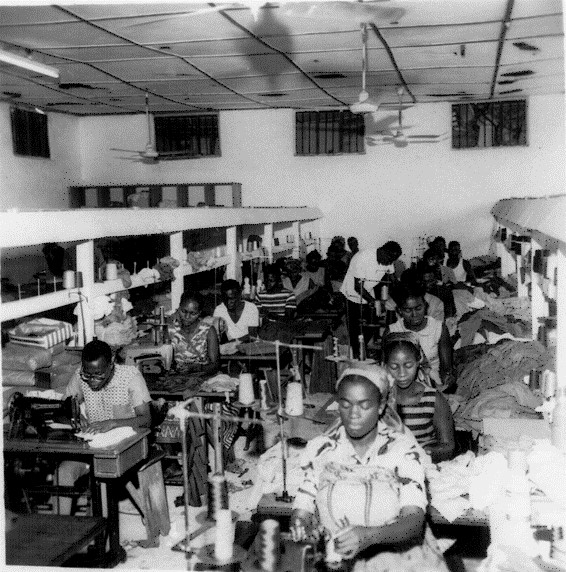

Making the way for Ghana’s Industrial Future

Sindhi manufacturers did not only produce goods but also created brand names such as Hi Honey, Love Bird, and Happy Go Lucky, which made their products easily identified on the market. They also introduced and promoted the idea of advertising products as “Made in Ghana.” Thus, it was not uncommon to see their garments bearing their uniquely-coined brand names and the “Made in Ghana” label. By the early 1960s, a Sindhi firm like Glamour Garment Factory employed over 500 workers, most of whom were Ghanaian skilled and unskilled workers (Figure 2). In terms of production, Glamour produced as many as 12,000 singlets, 1,800 blouses, 1,200 pairs of shorts, and 600 shirts daily in 1962. By the next decade, the factory was exporting garments to neighboring Togo and Nigeria. As the pioneer Sindhi industry in Ghana, Glamour was well represented in local exhibitions such as Ghana’s International Trade Fair, as well as international exhibitions. Sindhi manufacturers could achieve this commercial success due to their recognition of and active engagement with Nkrumah’s economic plans for the country. Ghana’s manufacturing sector collapsed over the next two decades due to political and economic factors, including structural adjustment policies. Currently, the only evidence of this once vibrant manufacturing industry is the Ring Road Light Industrial area, which has become an enclave of Ghana’s auto industry, which is dominated by Sindhis. This suggests and testifies to ever-changing transformation in economic roles for the Sindhi community in Ghana’s economic development.

Figure 2: Ghanaian workers at Glamour Garment Factory

Source: Photography Division of the Information Services Department, Accra

References

Brennan, James. Taifa: Making Nation and Race in Urban Tanzania. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2013.

Decker, Stephanie. Postcolonial Transition and Global Business History: British Multinational Companies in Ghana and Nigeria. New York: Routledge, 2023.

Falzon, Mark-Anthony. Cosmopolitan Connections: The Sindhi diaspora, 1860–2000. Leiden: Brill, 2004.

Fieldhouse, Daniel. Merchant Capital and Economic Decolonization: The United African Company, 1929–1987. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.

Murillo, Bianca. Market Encounters: Consumer Cultures in Twentieth Century Ghana. Athens, US: Ohio University Press, 2017.

Feature image: Glamour Garment Factory, credit: Information Services Department, Accra

Publisher: Source link