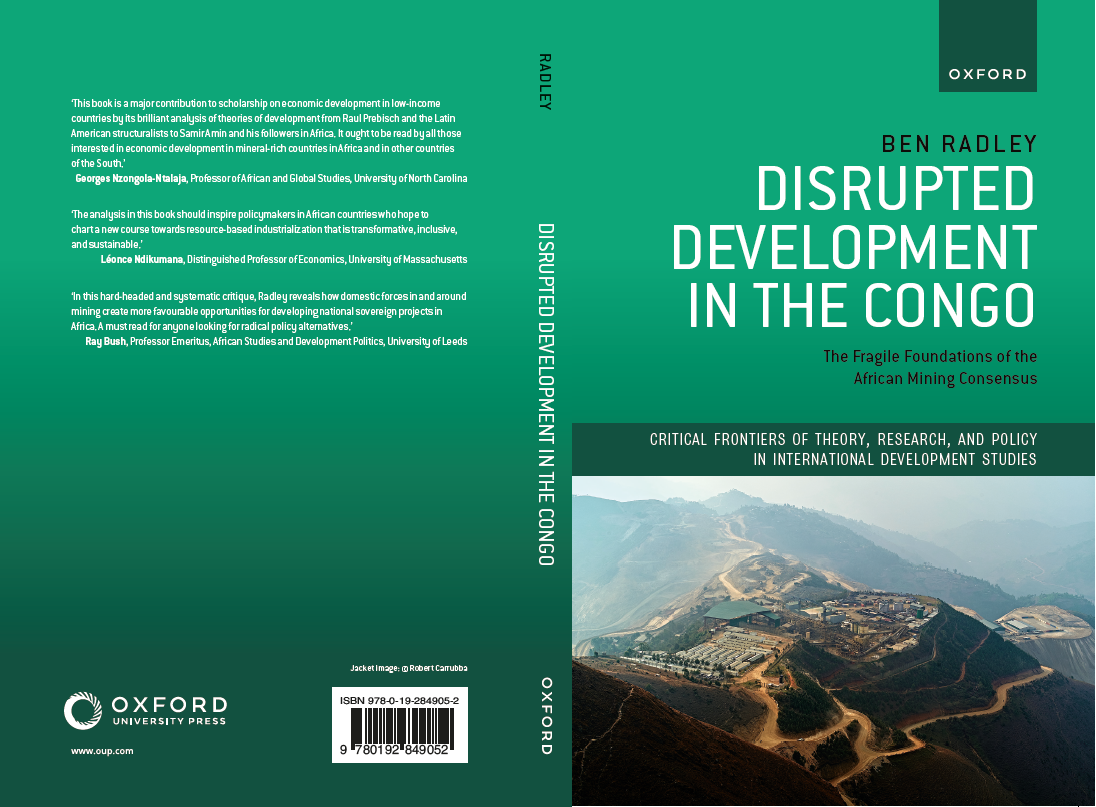

In the 1960s, newly independent African governments asserted sovereignty over their metal and mineral resources, in a reversal of their prior colonial exploitation by European mining corporations. In this excerpt from his new book Disrupted Development in the Congo: The Fragile Foundations of the African Mining Consensus, Ben Radley shows how transnational corporations have once again become the dominant force assuming ownership and management of industrial mining projects. Radley argues this latest reversal has taken place through a three-stage process grounded in a misguided reading of African economic stagnation from the mid-1970s onwards. Recent mining code revisions in several countries have been heralded by some as marking a new era of resource nationalism. Yet the new codes remain a far cry from the earlier period of resource sovereignty. The first three chapters of the book can be downloaded for free here.

Stage one: Blame the African state

The first wave of political independence in Africa, beginning in the mid-1950s, ushered in a period of resource sovereignty, including the pursuit of African socialism in several countries. This was based on the recognition that during the colonial period, Africa’s natural resources had been exploited by European mining corporations to the benefit of the colonizing countries. For these resources to serve the interest of African countries, economies, and peoples, it was held that external control and ownership had to be reduced. Buoyed by the long commodity boom of the 1950s, and the spirit of events such as the 1955 Bandung Conference and the 1958 All African People’s Conference, there was a general commitment by newly independent African governments to wrest the control and management of their natural resource wealth back from the hands of their former colonizers.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the first step was taken under the presidency of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu with the Bakajika Law of June 1966. This law was an explicit attack on the contentious 1960 Belgian law giving colonial Congolese corporations Belgian nationality just a few weeks before Independence. It required all foreign-based companies whose main activities were in the DRC to establish their headquarters in the DRC by the end of the year.

The government failed to reach an agreement on the nationality of the largest, Belgian-owned colonial mining subsidiary, Union minière de Haut Katanga. So, on 31 December 1966, the Mobutu administration announced its decision to expropriate the firm and transfer its assets to a new company, Société générale Congolaise des minerais (Gécamines), which was to eventually become 100 per cent state-owned. The policy of increasing state participation in the productive economy continued in other sectors. By 1970, the Congolese public sector controlled 40 per cent of national value added.

Efforts elsewhere were similarly ambitious, such as Kenneth Kaunda’s Zambian-led initiative of the Intergovernmental Council of Copper Exporting Countries (CIPEC) and Julius Nyerere’s nationalist ban on extractives, ‘aimed at keeping resources in the soil until the nation could develop the productive forces to manage extractives for national development’. Early results were impressive. In the DRC and Zambia, copper production increased steadily between 1960 and 1974—across the inaugural years of CIPEC—from around 300,000 to 500,000 tonnes and 500,000 to 700,000 tonnes, respectively.

In the DRC, greater sovereign control of value added contributed to a tripling of state revenue from $190 million in 1967 to $630 million in 1970, based in part on a 50 percent profit tax in the mining sector. A national health system numbering 500,000 employees was established, seen as a model for primary health care in the global South. The education system was nationalized, achieving 92 per cent primary school enrolment and increased access to the secondary and tertiary sectors.

The period culminated in May 1974 with the United Nations adoption of a Declaration and Programme of Action on the Establishment of a New International Economic Order. This declaration and programme ‘set out principles for equality between nations, including sovereignty over natural resources and an equitable relationship between the producers and consumers of raw materials’. Rather than usher in a new international economic order, however, the period during which this declaration was signed was to prove a stark reminder of the solidity of the old order.

The declaration was inaugurated at a time when the oil price was beginning to rise and demand for African exports beginning to diminish due to recession in the global North, leading to a decrease in commodity prices. In the DRC and Zambia, the copper price crashed from $1.40 per pound in April 1974 to $0.53 per pound in early 1975 and stagnated thereafter. Around the same time, from 1973 to 1977, the cost of oil imports quadrupled. Coupled with rising inflation globally during this period, the effect of these price shifts on government revenue would have been even greater in real terms. In addition, as African government loan repayments became due, interest rates on the loans began to rise as the United States sought to control inflation through monetary policy.

Previously rising mining production levels stagnated or dropped, growth slowed, and debt grew across the continent, reducing the foreign exchange available to purchase the imports needed to further industrialization. Between 1980 and 1988, 25 African countries rescheduled their debts 105 times. In the DRC, copper and cobalt exports decreased sharply, eventually collapsing by the early 1990s.

Of course, external shocks were not the sole cause of the reversal. Internal dynamics had a critical role to play. In the DRC, external shocks unmasked the failures and limitations of Mobutu’s nation state-building project. Nationalization measures undertaken in 1973 and 1974 to provide an emerging politico-commercial class of senior state bureaucrats with access to productive capital—known as Zairianization—were poorly planned and implemented and went badly awry. Agriculture had been neglected, receiving less than 1 per cent of state expenditure from 1968 to 1972, and the Congolese manufacturing sector was in decline.

Yet, a consideration of the impact of external shocks, alongside recognition of the progress made by newly independent African governments in the short time frame up until this juncture, was largely missing from influential analyses of the 1980s seeking to understand the causes of African economic stagnation from the mid-1970s onwards.

Instead, misguided African state intervention and government corruption were put forward as primary causal explanations, to the exclusion of other factors. Championed largely by Africanists based in North American universities (such as Robert Bates and Eliot Berg, the latter the author of the World Bank’s 1981 report Accelerated Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Plan for Action), this line of thinking was immediately embraced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

In the DRC, World Bank reports from the 1980s show how ingrained this view was at the time. In one, the Bank argued that the country’s economic decline was due to ‘a long series of inadequate economic and financial decisions. Nothing in the past decade has had a more lasting and devastating effect on the economy than the Zairianization and Nationalization measures of 1973 and 1974.’

There is no doubting that the ill-conceived nationalization policies of the 1970s held a share of the responsibility for the DRC’s economic difficulties during this period. Yet, such factors ought to be weighed in consideration with the impact of external shocks— which began for the DRC with the copper price crash in 1974—and the achievements made by the Mobutu administration up until this point. Such a weighting exercise is absent from both reports.

Offering a regional perspective, the seminal work of Mkandawire and Soludo on the causes of the mid-1970s decline in African economic performance is worth citing at length:

Our intention here is not to rationalize, let alone ignore the infamous mismanagement of economies by African governments. Rather, the point is to emphasize that successful adjustment will be elusive unless Africaʼs vulnerability to external factors is recognised. Such a recognition will serve in rethinking the form and content of Africaʼs structural transformation. Failure to account for such factors, even as one corrects for internal policy errors, can frustrate attempts at change and condemn them to involuntary reversal.

By downplaying the external and foregrounding the internal, the result is an analysis and diagnosis that lays the blame firmly on the state management and ownership structures underpinning national developmentalist ambitions in the 1960s and early 1970s, to the exclusion of external shocks and trends in the global economy.

With governments across the global South in debt distress, and with little or no access to international capital markets during this period, the IMF and the Bank grew significantly in influence, formulating a neoliberal set of now infamous policies that came to be known as the Washington Consensus. The policy doctrine of privatization, liberalization, and deregulation was implemented across Africa by World Bank and IMF-financed structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Crucially, most SAPs had a focus on increasing primary commodity exports, but this time around—to correct for the perceived failures of the recent past—under new management.

Stage two: Liberalize and privatize

It was in this neoliberal political and ideological context that, as Hormeku-Ajei and Goetz have summarized, ‘the World Bank told African governments to abandon any notion to use mineral resources to serve social priorities or developmental priorities and give up the running and management of minerals and mineral wealth to transnational companies’. Between 1980 and 2021, the Bank provided $1.1 billion in mining sector grants and loans to fifteen of the continent’s seventeen mineral-rich, low-income countries (LICs) (Table 1).

Table 1 African LIC metal and mineral wealth

| Insignificant or modest | High |

| Benin, Burundi, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan | Burkina Faso, Central African Republic (CAR), Chad, DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda |

Sources: Author classification based on the World Bank’s fiscal year 2020 country classifications by income level, US Geological Survey country reports, and The Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining Knowledge Sharing Archive.

Prior to the rise of China as an alternative source of resource-linked finance, and with many African countries still unable to access international capital markets, the Bank was able to exert significant influence through these grants and loans to implement its strategic vision for how mining should be organized and managed, as laid out in its 1992 Strategy for African Miningreport:

The private sector should take the lead. Private investors should own and operate mines…. Existing state mining companies should be privatized at the earliest opportunity to improve productivity of the operations and to give a clear signal to investors with respect to the governmentʼs intention to follow a private-sector-based strategy.

In the DRC, staff from the Bank worked in close collaboration with a Congolese committee on the drafting of the mining law. Blaming mining-sector decline on poor governance under the Mobutu administration, the eventual 2002 Mining Code moved to privatize state-owned mining enterprises and attract fresh foreign direct investment (FDI) by offering a generously liberal fiscal regime, including tax holidays and exemptions and low royalty rates. This included the eventual privatization of the country’s two largest SOEs, the copper producer Gécamines and the diamond producer Société minière de Bakwanga.

Three decades on, the underlying logic of the Bank’s African mining strategy continues to hold. In 2021, the Bank had ongoing mining reform programmes in the seven mineral-rich, African LICs of Niger ($100 million), Guinea ($65 million), Mozambique ($50 million), Mali ($40 million), Sierra Leone ($20 million), Togo ($15 million), and the Central African Republic ($10 million). Each programme was focused, in whole or in part, on institutional and regulatory change within a general framework giving overall priority to capital-intensive, foreign-owned mining.

With the regulatory framework overhauled, foreign investment was unleashed to seek out fresh opportunities. Mining exploration in Africa increased from 4 per cent of total mineral exploration expenditure worldwide in 1991 to 17.5 per cent in 1998, and overall mining investment in Africa doubled between 1990 and 1997. The start of a commodity supercycle in 1999 gave fresh impetus to this activity. In 2004, the $15 billion invested in mining in Africa represented 15 per cent of the total of mining investment worldwide, up from 5 per cent in the mid-1980s and putting the region third globally, behind Latin America and Oceania. From 2002 to 2012, a period spanning most of the supercycle, mineral exploration spending in Africa rose by more than 700 per cent, reaching $3.1 billion in 2012.

In 2007, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) noted that:

the sweeping changes in African mining policy in the 1980s and 1990s were aimed at attracting FDI and increasing exports, in which they have been successful. Total FDI inflows into African least-developed countries rose fourfold from an annual average of $1.7 billion in the 1990s to $6.8 billion in 2000 to 2005…the bulk of which was directed to mineral extractive industries.

In the DRC, FDI inflows focused almost exclusively on mining, increasing by a factor of seventeen between 2002 and 2012, from $188 million to $3.3 billion. Across the same period, FDI stocks rose from $907 million to $22.5 billion or from 10 per cent to 59 per cent of gross domestic product.

Looking at the aggregate level of inward FDI flows to the group of 17 mineral-rich, African LICs from 1970 to 2019 confirms this picture. Total FDI inflows to the group were low and stable during the 1970s and 1980s, at an annual average of just $0.2 billion, increasing only slightly to $0.6 billion in the 1990s. Hereafter, they grew to an annual average of $3.9 billion in the 2000s and $13.9 billion in the 2010s.

At the country level, FDI inflows have grown significantly across all 17 countries from this group, with the sole exception of Eritrea. While countries such as Madagascar, Guinea, Mali, Sierra Leone, Malawi, Togo, and Burkina Faso received the lowest levels of foreign investment across the group, they have nonetheless experienced pronounced increases in these flows since the turn of the century, much of which has been mineral-seeking. And as highlighted earlier, it is in several of these lower-placed countries that, in 2021, the World Bank had active mining sector liberalization and privatization programmes.

The dramatic increase in FDI growth since the 1990s has altered the composition of these economies, which have become increasingly dependent upon FDI as a source of development financing, and this level of dependence is greater today relative to other country groups and regions.

Stage three: Criminalize African miners

One final stage was required before transnational mining corporations could move front and centre. This involved dealing with the on-the-ground reality that, for many incoming transnationals, their prized deposits were already occupied by African miners involved in a wide range of labour-intensive forms of mining. Most commonly associated with gold and diamonds, labour-intensive African mining is also involved in the production of silver, copper, cobalt, tin, tantalum, iron ore, aluminium, tungsten, wolframite, phosphates, precious and semi-precious stones, and rare earth minerals, among others. Globally, labour-intensive mining has been estimated to contribute up to 30 per cent of total cobalt production, 25 per cent for tin, tantalum, and diamonds, 20 per cent for gold, and 80 per cent for sapphires.

Labour-intensive African mining has grown significantly since the 1980s to directly employ millions of workers across the continent, driven by three factors. First, the crisis of African agriculture has led to an increasingly important role for off-farm employment. Second, the decline of state-led national developmentalism and the collapse of welfare provisioning under the weight of structural adjustment during the 1980s exerted significant strain on the productive and reproductive capacity of rural African households. Third, rising commodity prices, especially during the supercycle of 1999–2012, pulled people towards the sector, where there were often higher wages and profits to be made than locally available alternatives.

Despite the sector’s importance to rural employment, African miners have typically been cast by the World Bank, African governments, and parts of the scholarly literature as ‘primitive’, ‘basic’, ‘inefficient’, ‘rudimentary’, and ‘unproductive’ (in contrast to the ‘efficient’, ‘modern’, ‘complex’,

and ‘productive’ mining corporation). As a result, labour-intensive African mining has been peripheral to mining development strategies on the continent. Criminalized by policy frameworks unless they submit to a set of procedurally complex, bureaucratically burdensome, and financially costly demands to formalize their activities, and cast as illegally encroaching on a concession once it has been assigned to a corporation, African miners have time and time again been forcibly displaced from their sites to make way for the construction of corporate-led industrial mines. Often financed by the incoming corporations themselves, and echoing violent colonial practices of the past, displacement has frequently taken place as government military-led ‘sweeps’.

In 2017, 70,000 miners were displaced by Ugandan military and police in Mubende to make way for a Canadian-listed mining corporation. Speaking to local media shortly after the displacement, Edwards Katto, a Director at the Ugandan Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, said:

Those people [Ugandan miners] still joking should style up. Now, I’m not only a director [in the Ministry] but also a commander of the Minerals Protection Unit of the Uganda Police Force. So, those illegal miners still behaving like those in Mubende [who were evicted], they should pack and vacate the mines, otherwise, my police force will them help to pack.

This statement speaks well to the general regard held for African miners within the process of capital-intensive, foreign-owned mining (re)industrialization. These dynamics recall Marx’s description of primitive accumulation, or Harvey’s (2004: 74) reconceptualization of this as a continuous process of accumulation by dispossession, involving ‘the commodification and privatization of land and the forceful expulsion of peasant populations, conversion of various forms of property rights into exclusive private property rights, [and] suppression of rights to the commons’. Forcibly displaced and removed from the best deposits, African miners are restricted to working in less productive areas.

With the African state framed as corrupt and mismanaged, and African miners as inefficient and unproductive criminals, the path was cleared for the en masse arrival of transnational mining corporations, across a far wider group of countries than was the case during the colonial period (when most mineral deposits remained unknown to foreign capital, particularly in West Africa). From Glencore and Pengxin in the DRC and Emirates Global Aluminium in Guineau, to Cluff Minerals and Etruscan Resources in Burkina Faso and Shandong Iron in Sierra Leone, to AngloGold Ashanti and Acacia Mining in Tanzania and Rio Tinto in Madagascar – the list goes on – foreign corporations dominate today’s landscape.

Recent mining code and policy revisions led by African governments such as Tanzania, the DRC, Sierra Leone, and Malawi have begun to push back against this dominance, taking inspiration from the Africa Mining Vision, a framework developed by the African Union in 2009 to deepen the linkages between foreign-owned mining and national economies and strengthen government capacity to negotiate with and leverage developmental benefits from foreign mining corporations.

The mining industry and some scholarship has been quick to herald these revisions as marking a new era of resource nationalism. As a Bloomberg article proclaimed in 2019, ‘The fight between miners and African governments is just getting started’. Changes to date are yet, however, to provide a fundamental challenge to the dominant model of capital-intensive, foreign-owned mining industrialization on the continent. They remain a far cry from the earlier period of 1960s and 1970s resource sovereignty to which the discourse on resource nationalism alludes.

Ben Radley (@RadleyBen) is a Lecturer in International Development at the University of Bath. His research interests relate to the political economy of economic transformation in Africa, with a focus on resource-based industrialisation, green transitions, and labour dynamics. He’s a member of the Editorial Working Group for ROAPE, and an affiliated member of the Centre of Mining Research at the Catholic University of Bukavu, DR Congo.

This excerpt was originally posted here on www.roape.net.

Publisher: Source link