By Robrecht Declercq & Duncan Money

7 January 1968 was a day of celebration across the Congolese Copperbelt, marked with marches and festivities in the mining towns, bonuses for mineworkers and medals for those who had labored many years in the industry. All this marked the one-year anniversary of the foundation of Gécamines, the state-owned company that was established when the Congolese government nationalized the operations of Union Minière du Haut Katanga (UMHK).

Early in 1967, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) had decided to nationalize the largest and most powerful colonial company that still operated on its soil, after a dispute about where the headquarters of the company should reside. But deeper concerns stemmed from the fact that a former colonial business still controlled the most important natural treasures of the newly independent Congo. The Congolese had high hopes that the new company would propel economic growth through significant expansion of production. Ultimately, these hopes met with bitter disappointment.

It was not only Congolese people who entertained such hopes, however. What happened in Congo was part of what we term a post-colonial world of copper (1960-1980) in our edited collection Born with a Copper Spoon. The book is a history of the global production of copper, its labour relations, technologies and the international political economy across the 19th and 20th century. The transition, and ultimately, failure of this unique albeit brief episode of postcolonial control is one of the focuses of the book. We assert that the national fragmentation of copper production in the postcolonial world, was in fact deeply intertwined with transnational influences and exchanges. It expressed an agenda that was shared in the Global South: to straighten out the huge economic imbalances with the Global North.

The nationalization of UMHK was contagious. Zambia nationalized the mines in 1969, Chile did so in 1971 while the military junta of Peru nationalized the mines of Cerro de Pasco in 1973. Within a span of a few years, control over the industry in the world’s four-largest copper exporters had passed from American and European multinationals to newly-assertive states. The postcolonial world of copper embodied economic sovereignty, state-led national development schemes and international co-operation. It was pursued by military juntas, dictators and socialist-inspired leaders alike. In all these countries, the red metal symbolized the national treasury, the material of progress. As Zambia’s President Kenneth Kaunda remarked, Zambians were “born with a copper spoon in our mouths.”

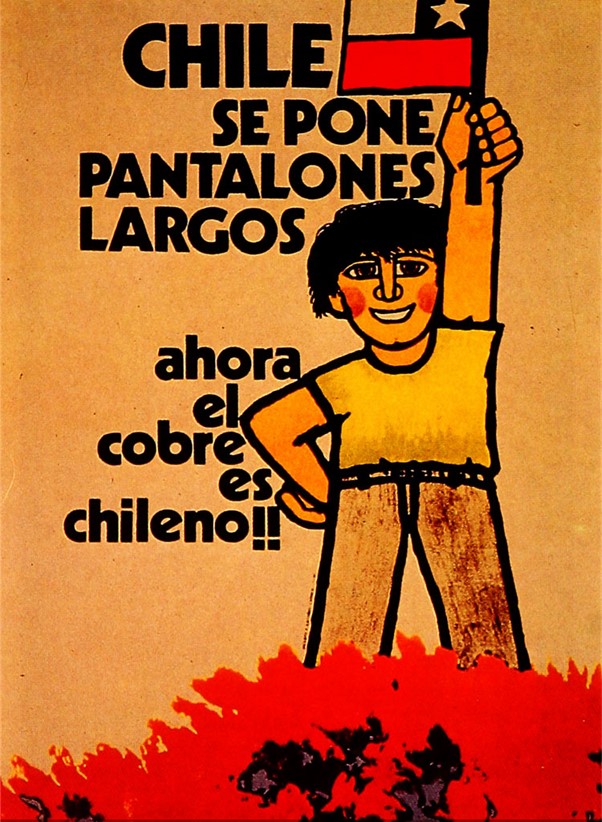

The nationalizations were celebrated in the copper states as a re-birth of the nation, an expression of true ‘independence’. After political sovereignty, countries established economic sovereignty. In Chile, stamps, postcards, paintings celebrated the nationalization of the copper seams as a major achievement. Songs were made. One remarkable postcard equaled the control over copper with the coming-of-age of Chile as a modern and developed state, no longer in a state of dependency: “Chile se pone pantalones largos (…) ahora el cobre es chileno”. These vivid expressions were no less different than the carefully orchestrated celebrations held in Congo.

This was no less than a revolutionary overhaul of an older world of copper, one we term in our book the ‘American world of copper’ that endured from the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. The international copper industry was not only dominated by American firms (with some notable exceptions) in these years but also by American-born ideas of company structures, technologies and labor practices.

American dominance over the copper industry emerged alongside an enormous increase in demand for copper during the Second Industrial Revolution. Electrification required copper to generate and distribute power, and output rose enormously. World copper production was about 55,000 tons in 1850 and almost 900,000 tons in 1910.

Over the late 19th century, the American world of copper spawned huge multinational companies that developed a firm grip over new copper mines in Latin America and Central Africa. How these companies operated in different places was remarkably similar: an oppressive paternalistic control that sought control over virtually all the aspects of workers lives and an unhealthy influence of (domestic) politics. Copper companies controlled the entire chain: from mine to consumer was the slogan of the notorious Anaconda copper company that operated in Montana and Chile.

But in the 1960 and 1970s copper states took their place. Importantly, copper states were aware of the fact that domestic control did not suffice. On the initiative of Zambia, copper states established an international cartel in 1967: CIPEC (Conseil intergouvernemental des pays exportateurs de cuivre). The acronym was an obvious reference to the oil cartel OPEC that had upended the global oil industry.

Much like its more famous counterpart, the CIPEC aimed to control the price of copper by coordinating production between the major exporters. This was part of broader efforts by producer nations to contest the structure of the world economy and take advantage that industrialized economies had on raw materials from elsewhere. European economies in particular were heavily dependent on copper imported from CIPEC members.

CIPEC’s membership soon expanded too. In 1975, Papua New Guinea and Indonesia together with Yugoslavia and even Australia joined CIPEC. The control over commodities like copper seemed to offer a tangible way to actually reform the global economy. Indeed, industries could ill-afford to be cut from metals and energy sources like oil.

CIPEC also showed remarkable continuities. Mining multinationals during the American world of copper had endeavored to control global copper production to support prices and revenues. Yet they had found this an extremely difficult task, an inauspicious legacy for CIPEC.

By the late 1970s, the bid for state-controlled and internationally coordinated growth based on copper tragically failed. Unlike OPEC, CIPEC controlled an insufficient portion of global production and couldn’t discipline member states to stick to planned production cuts. Moreover, once the world economy went into decline after the Oil Crisis of 1973, international copper prices slid into the abyss, causing massive problems in the copper-producing states.

Gécamines still exists today, but in a very different form. Its demise encapsulated the end of post-colonial world of copper. After two decades of low copper prices, its operations were privatized under a World Bank program in the early 2000s. Congo’s mines today are owned and operated by large multinational corporations (plus some state-owned Chinese companies).

Born with a Copper Spoon describes this moment of postcolonial world of copper, both its intense feelings of nationalism and the international cooperation it entailed. Ultimately what happened in the copper mines in Africa and Latin America was salient in the important bid of the Global South to straighten out the huge imbalances of the world economy, which culminated in a program of action called the New International Economic Order (NIEO).

The underlying ambitions and ideas of the postcolonial world of copper have far from disappeared. The sovereignty of natural resources has become much more widely accepted. Furthermore, the situation of today demonstrates important parallels with historical periods in the copper industry: an energy transition that will require enormous quantities of copper, wide anticipation of prolonged high copper prices and states around the world taking a greater role in the industry. A new world of copper is in the making?

Robrecht Declercq is a historian, writer, and lecturer at the UCL-Saint Louis de Bruxelles.

Duncan Money is a freelance historian and consultant and his work focuses on the mining industry.

Publisher: Source link