In this paper we study 500 years of African economic history using traveller accounts. Applying modern day computational linguistic techniques in combination with domain knowledge of African economic history, we analyse how first-hand accounts evolve across space and time. We illustrate how this database can be used, by showing how it sheds light on the effect of quinine adoption on European expansion in Africa, and how it allows us to trace the diffusion of New World crops in Africa, particularly maize.

Over the past two decades, African Economic History research has surged. Many studies focus on the colonial period when bureaucratic apparatuses became developed enough to produce government documents. The precolonial period, in contrast, has remained underrepresented due to the dearth of sources that scholars could engage with. In a recent article, we explore a source that can potentially shed new light on 500 years of Africa’s precolonial past: travel diaries.

Africanist historians view these diaries with scepticism, noting that they were written for European audiences and reflect subjective biases and the social norms of their time. However, the very same criticism can be extended to governmental records produced by colonial regimes such as Blue Books and Censuses, which also catered to European interests. While we acknowledge the limitations, one must be careful not to throw out the baby with the bathwater by dismissing the source and the information that it offers in its entirety (Frankema & van Waijenburg, 2023).

Building the Database of “Travellers of Africa”

A directory of travellers to Africa did not exist. Hence, we built one from scratch. We began by searching three major online repositories: Internet Archive, Gallica, and Google Books. We used the following combination of search terms:

(voyage* OR exploration* OR expedition* OR travel* OR survey* OR excursion*) AND LOCATION AND (date: 1200 TO 1900 OR NA) AND (mediatype = texts), where LOCATION is defined from a compiled list of historical names of African regions and territories.

Additionally, we manually searched several secondary sources. We restricted our analysis to English texts processed with Optical Character Recognition (OCR). At the end, this resulted in 855 documents from 712 journeys by 605 travellers, totalling 237,741 pages and 30,140,114 tokens (text units like single words but excluding stop-words like “the”, “that”, “and”). This is BIG Data in African Economic History! Finally, we hand-coded metadata variables for each document: the traveller’s occupation and nationality; regions and countries visited; journey and publication date; and publication details.

As this new database is intended for public use, our article provides a detailed summary of the travellers’ backgrounds and the spatial and temporal scope of the collection. For content analysis, we applied Structural Topic Modelling (STM), a method that groups words that often appear together, allowing us to detect common themes, and to understand how these topics evolve across space and time, and vary across authors’ backgrounds. Using text analytical tools, our data base can be employed to assist in answering long-standing debates in economic history.

Quinine

It is widely believed that malaria prevented European control over Africa by exerting a prohibitively high death toll on any attempt to exert control (Curtin, 1998). Previous works studied survival rates of European soldiers, employees of the Royal African Company and Christian missionaries.

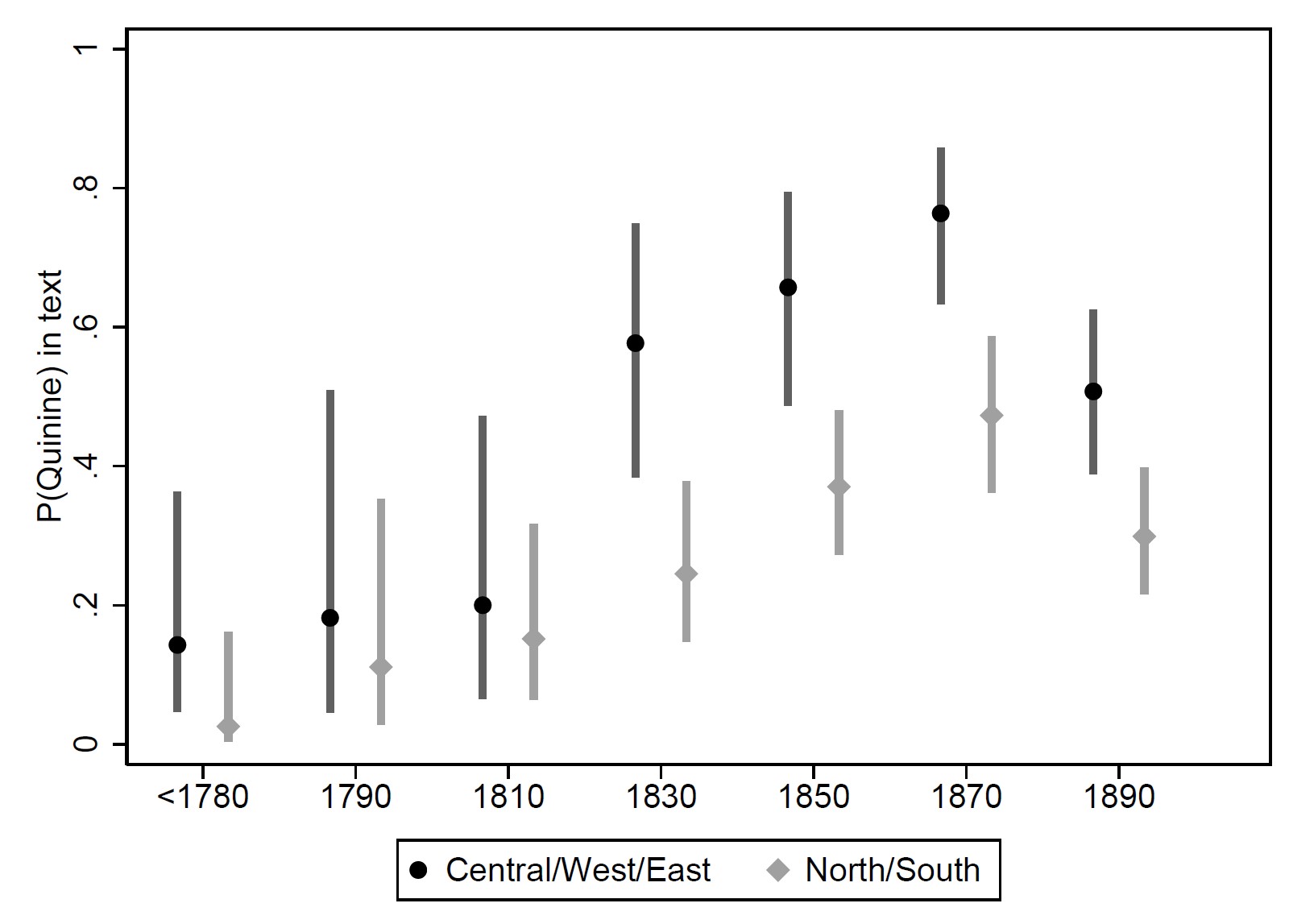

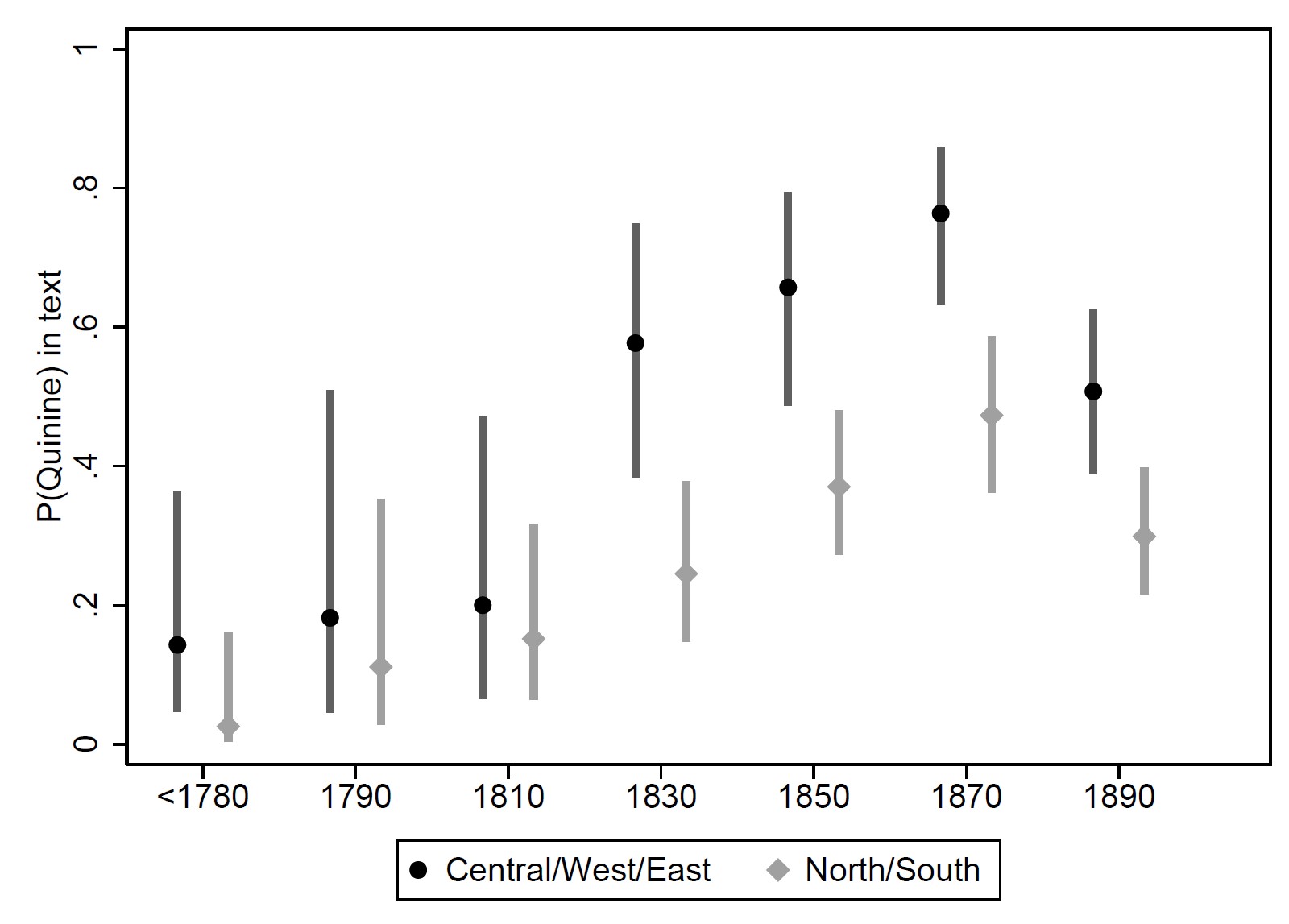

When did malaria remedies spread? We created a dictionary containing words associated with malaria treatments based on the bark of the quina-quina tree. Figure 1 illustrates word prevalence over time and space. We find quinine and related words appear always more frequently in travel diaries to high-malaria-risk areas of Africa (Central/West/East) than in lower-risk areas (North/South). Notably, even before 1820, 20% of travellers to Central/West/East Africa mentioned potentially effective treatments in their texts. The use of quinine increased significantly from 1820-1840 in both regions, but more steeply in Central/West/East, reaching around 80% by the 1870s. Around 1890, quinine word prevalence declined. This may reflect an actual decrease in the use of quinine, after an intense public debate emerged during the 1890s raising doubts about the safety of quinine and its potential connection to the occurrence of blackwater fever (Wells, 2018).

Did quinine facilitate European expansion into Africa? Malaria disabled travellers, and forced them to return early. To examine this, we use the number of tokens in the documents as a proxy for journey length. The positive correlation between the number of tokens and the number of African countries travelled (corr: 0.15***) supports this interpretation. We found a significant 47% increase in document length when the word “quinine” was prevalent in the document. The effect differed spatially. With a reference to quinine, the number of tokens increased by 38% and 65% in lower-risk and high-risk regions, respectively.

Figure 1. Prevalence of quinine words in the texts

Notes: Figure 1 shows word prevalence, and the 95% confidence interval, over time in high and lower malaria-risk regions of Africa (Central/West/East and North/South respectively).

Columbian Exchange

Maize was a New World crop that offered several advantages over traditional African grains. Maize adapts well to diverse climatic conditions and could be grown on soils that, prior to 1492, were marginal because of sandiness, altitude and aridity (Crosby, 1972). Maize boasted higher yields compared to sorghum and millet and it was easier to harvest and process into flour and porridge. Knowledge about the points of entry and patterns of diffusion is limited.

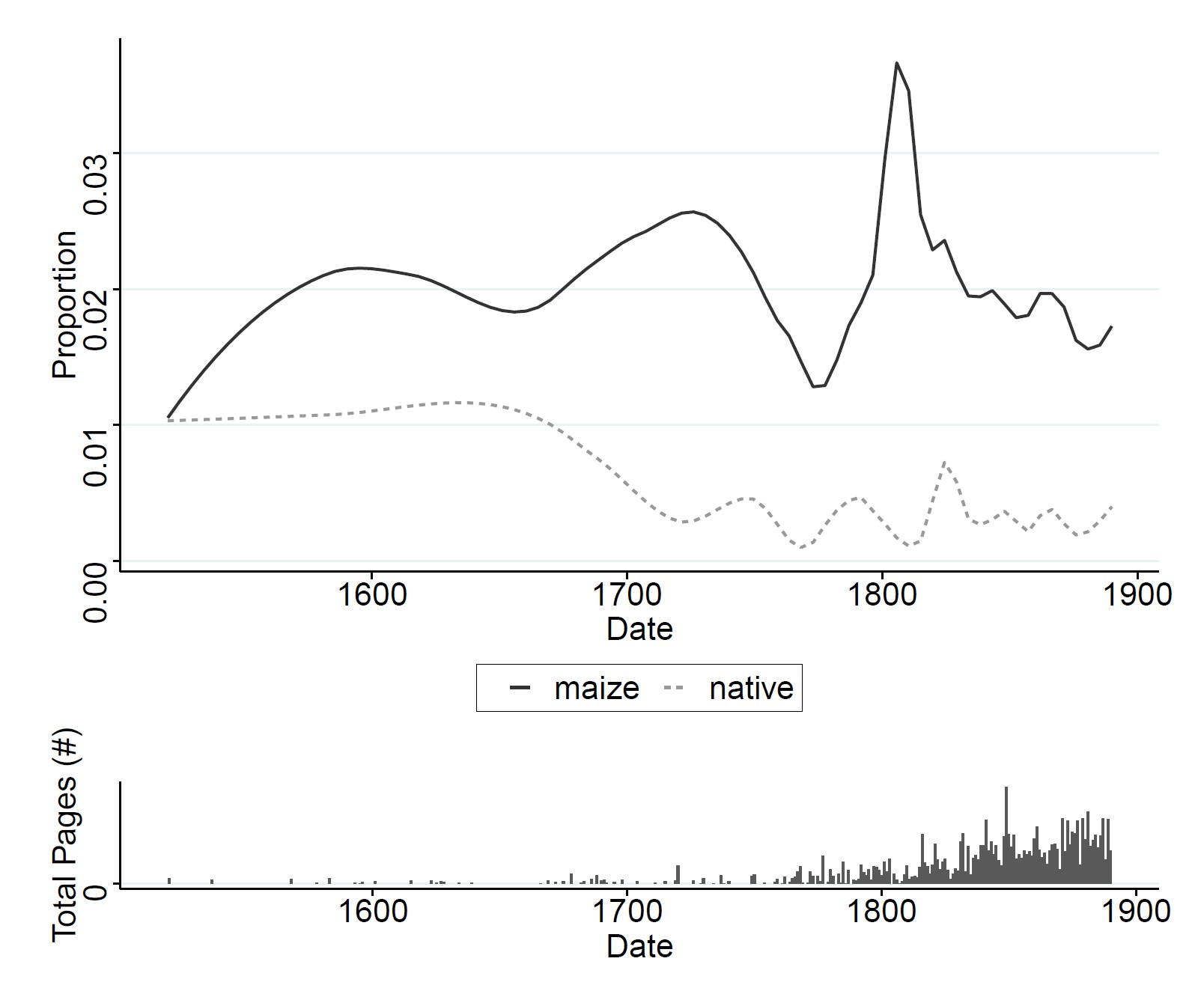

Searching for mentions of maize and the two most prevalent native grains, sorghum and millet, we first uncovered the diverse nomenclature for maize across Africa, compiling a dictionary of 147 synonyms for maize. Of all the synonyms, ‘corn’ was the most prevalent (82%), yielding 11,039 hits from a possible 220,000 pages (10%). The crop was mentioned by the Portuguese traveller Alvarez as early as 1520. A surprisingly large proportion of journeys in their corpus contained some reference to maize (623 out of 712). Figure 2 shows that maize mentions per tokens increased much faster than native crops, which decline in proportion and become almost inconsequential in the latter parts of the 19th century. This suggests that the crop was rapidly adopted and came to dominate the diets of many Africans by 1700.

Figure 2. Relative page mentions maize and native crops in text

References

Crosby, A. W. (1972). The Columbian exchange; biological and cultural consequences of 1492. Greenwood Pub. Co.

Curtin, P. D. (1998). Disease and empire : the health of European troops in the conquest of Africa. Cambridge University Press.

Frankema, E., & van Waijenburg, M. (2023). Bridging the Gap with the ‘New’ Economic History of Africa. The Journal of African History, 64(1), 38-61.

Wells, J. M. (2018). Quinine, Whisky, and Epsom Salts: Amateur Medical Treatment in the White Settler Communities of British East and South-Central Africa, 1890–1939. Social History of Medicine, 33(2), 586-603.

Feature image: From Supan (Die Fortschritte der Afrikaforschung, 1888) showing the expanding knowledge of Africa in the Western world.

Publisher: Source link