Response to Thomas Meaney, “Red Power” in LRB (Vol. 46, No. 14, 18 July 2024)

In the latest issue of the London Review of Books under the title of “Red Power: Indigenous Political Strategies,” Thomas Meaney has written a review of three recent award-winning books by historians of Native North America: Pekka Hämäläinen’s Indigenous Continent; Ned Blackhawk’s The Rediscovery of America; and Nick Estes Our History is the Future. In some ways, the review is impressively learned. Meaney uses the occasion to canvass a generations-spanning array of scholarship on the history of Native North America and engages figures, events, and historiographic questions of which only a very small body of Native and non-native scholars on these topics are even aware.

Marks of erudition aside, Meaney is out to weave together a broader narrative that extends beyond the historical bona fides of these books. The key moment in setting up this narrative comes after Meaney has raised his readers’ hopes by opening with a quite historically literate summary of European settler expansionism and Indigenous peoples’ responses to it. In the paragraph that then really begins the substance of his review, Meaney pivots: “but recent roadmaps of the historiography either sidestep material questions or mistake a colonized mindset for progressivist one.” This is where Meaney divides the three books under review into three categories of political and historical errors: Hämäläinen’s revisionist history overstretches the notion of “empire” in his account of “Indigenous power” by labeling the Lakota (and in earlier work, the Comanche) as such. (I agree with this critique, so I leave it aside in this review). Blackhawk represents a trend of scholars of Native history and federal Indian law who “have so thoroughly internalized constitutional ideology that they seem not to notice how their cause has been instrumentalized by the most fanatically libertarian segment of American society.” And finally, “a nominally [!] left-wing Native scholarship” that romanticizes Indigenous experiences, engaging in a politics of authenticity. The latter is how Meaney represents the work of Lakota scholar Nick Estes.

After establishing these categories, Meaney argues that these various limitations are “all the more regrettable because the 20th century offered examples of Indigenous co-operation with the left, cases contemporary political theorists have examined with more care than their historian peers.” This is a strange thing to assert at the outset, given that there was no recognizable anticolonial “left” in the US settler colony that Native nations could possibly have “cooperated” with in the 19th century. The consensus on the necessity and inevitability of land dispossession and structural predation cut across almost all categories of white society, including almost all of those on the far left of the political spectrum. Moreover, this included, as many others have noted, some key figures in the history of African-American political thought such as Douglas and Du Bois. What these historians—particularly Blackhawk and Estes—ask us to do is to suspend some assumptions about what constitutes the commitments of “the left” at all, given the deep investments of American republicanism and many later iterations of US leftism (let alone the liberalism of the Democratic Party) in colonial dispossession or just racialized indifference.

A Disappointing, Eurocentric Left Reading

I felt compelled to write this response to Meaney not only because I suspect that I am perhaps one of the unnamed “contemporary political theorists” he compares favorably to our “historian peers ” (he has a section based on material clearly from my book, Remapping Sovereignty), but also, more importantly, because I find the review to be deeply symptomatic of the troubling ways that (usually white, usually white male, always global north, usually nominally leftist) scholars and activists continue to talk down to Native thinkers and movements in ways that reconfirm their own sense of how to make proper political judgments “from the left.” It is as if Meaney has read this work (and, as I mentioned, he really has read quite a lot of it) while letting all the categories through which he sees the political and social world remain totally unchanged and unchallenged by the claims of the work itself.

Again, I find this to be all-too symptomatic. This is an orientation that seems to pop up across many other discourses in the western left, where the failure to actually internalize the lessons of Third World and Fourth World Marxisms and progressive movements shows up again and again in the almost comical provincialism of western debates. While the Palestine liberation movement has activated the most capacious transnational solidarity protests we have seen connecting core and periphery since the 1970s and while Israel obliterates the people of Gaza and their remaining social and environmental infrastructure, many of my western colleagues—again, even those on the nominal left or progressive wing of the Democratic Party—wring their hands and lecture Hamas and the PFLP on the right ways to resist colonial occupation. Perhaps discourse on the failures of “the left” in the core could be redirected constructively towards unequivocally lending support to the most important and expansive expression of left internationalist movement in recent years? And the same generosity and solidarity could be extended to anti-colonial movements here where I sit in the region of Nayaano-nibiimaang Gichigamiin (Great Lakes, in Anishinaabe language) and across Turtle Island (the so-called United States and Canada).

Here, like those engaged in a series of narrow debates about fascism, “eco-modernism” vs. “degrowth” approaches to the climate crisis, about race and class, and other topics that bear little relation to the realities of a global working class majority subject to the hierarchies of capitalist accumulation on a world scale, Meaney is among a set of (again, usually white, usually white male) analysts who “do the work” (as the phrase goes). Still, they cannot seem to confront the ways that the dynamics of white supremacy, settler colonialism, and imperialism fundamentally scramble the received historical coordinates of a phantasmagorically self-propelling European Marxism. This is a tradition so cut off from the rest of the world by its immersion in its own crises that it simply ignores the strongest pockets of resistance to neoliberalism, from present-day Kenya to Palestine. So, its historiographic and interpretive sensibilities remain skewed towards an almost laughably insular form of Eurocentric critique. In tandem with this, their expressions of solidarity and internationalism (even within the core vis-a-vis colonized Indigenous nations) remain tendentiously limited by their own self-cultivated horizons. The periphery—whether in or outside the geographic core—stays evermore interpretively and politically, well, peripheral.

Taking Power and History (more) Seriously in (US Settler) Colonialism

To get back to the text more narrowly, let me start with Meaney’s take on Ned Blackhawk’s book. It is strange that Meaney indicts Blackhawk for the sin of his “liberal legalist orientation” and at the same time condemns other scholarship, to his mind more suitably “left wing,” as resisting self-criticism in the form of “historicising native experience” itself. But this misses the point of both kinds of scholarship. A key claim of Blackhawk’s unparalleled work is that “native experience itself” is mediated by the complex task of navigating US political and legal structures, which in turn have evolved in ways that counter and channel Native agency. Meaney may not like that focus, but it hardly can be said to sidestep “material questions.”

In Meaney’s characterization of Ned Blackhawk’s panoramic history of Native North America, which spans from the 15th century to the present day, he argues that Blackhawk boxes himself in to the ideological confines of US liberal constitutionalism—that he “ends up embracing the co-optive limits of the US constitutional order.” As an historical claim, Meaney is at his strongest in suggesting that Blackhawk could spend more time talking about the economic dimensions of expansion (land speculation, settler land- and resource rushes, etc.) that often outran US state-formation. But the contemporary political and legal implications that Meaney reads into this are strange at best, first of all, because Blackhawk nowhere endorses any kind of US constitutional fetishism (to use Aziz Rana’s term), let alone could he be accused of an untutored embrace of a superficially “liberal” interpretation of the constitution. (Meaney never mentions the possibility of progressive, popular, or even decolonial accounts of constitutionalism, which would seem more relevant here than liberal constitutionalism per se.)

Blackhawk—and in my experience the vast majority of other scholars of federal Indian law and history—are better aware than anyone of the deep ironies and frustrations that haunt the work they do within and against the courts and institutions of the conquerors. Likewise, when Meaney goes on to describe (unidentified) “Native scholars” who reacted with at least momentary appreciation of uber-conservative Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch’s pro-Native decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), he suggests that they are endorsing positions that prop up conservative originalism (of a libertarian variety, in Gorsuch’s case). This is a strange interpretation, as it seems to insinuate that the fault lies with Native peoples and scholars for attempting to navigate a constitutional structure that is itself created through settler-colonial practices. Why does it follow that they would need to endorse the principles underlying Gorsuch’s decision in any other cases—or that they are implicitly and inadvertently doing so in writing approvingly of his decision in McGirt?

The answer is that they would not and do not need to go there, because it is just not the case that scholars’ and activists’ navigation of the bizarre child of American colonialism that is federal Indian law are required to sort those engagements into a prefabricated bucket of “progressive” vs “conservative” criteria for political judgment. Moreover, in isolating responses to Gorsuch’s decision in McGirt, Meaney has failed spectacularly to pay attention to another key case that shows he is just empirically wrong about any supposed alignment—discursive or otherwise—between right libertarian forces and “Indigenous originalists.” As the Cherokee journalist Rebecca Nagle and her team have brilliantly chronicled in great depth on the second season of the podcast This Land, the forces behind a challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act in Haaland v. Brackeen made up a “who’s who” of right-wing legal firms, dark money-infused foundations, and casino and oil interests with reactionary libertarian leanings. They wanted to dismantle tribal sovereignty because tribes have gotten a small piece of the pie, which they do in order to overcome colonial dependency relations, grow social infrastructure, and ensure the welfare of their citizens by investing in these industries. In navigating the contradictions of colonial-capitalism through these and other routes, Indigenous movements securing tribal land bases (from reform-oriented to more radical and revolutionary) are opponents of the reactionary right the vast majority of the time. Contrary to Meaney’s interpolation of the “left,” the right is very clear about who they hope(d) to be the easy victims of racial capitalist dispossession.

Patronizing Epistemic Demands on Indigenous Societies

As already suggested, the strangeness of Meaney’s assessment relates to the fact that an adequate analysis of the politics of settler colonialism (and frankly many other modes of racial and colonial domination) often demands that theorists coming from a broadly western leftist set of normative political assumptions actively recalibrate what counts as a “progressive” or “reactionary” political activity given the context. For example, tribal citizenship requirements might include restrictive membership inherited from colonial blood quantum regimes. Meaney is disturbed as a good leftist that “no other group in America is so fixated on blood percentages as Native Americans,” clearly indicating that this “fixation” locks in forms of ethnonationalist and racist exclusion in tribal politics. Referring to Robert Nichols’ 2020 Theft is Property!, he insists that we pay attention to “actual Native hierarchies and ways of doing business.”While these issues are complicated and fraught and worthy of analysis, it is odd at best—patronizing at worst—to say that a colonial regime of racialization that has worked to dispossess Indigenous peoples of land by blood quantum should then be framed as a “fixation” of Native peoples themselves. Moreover, Nichols does not set out to somehow represent contemporary Indigenous politics per se, but is quite straightforward that his project tracks a mode of “Indigenous structural critique.”

Given the historical conditions in which they find themselves as a result of colonial domination, many groups do have to navigate how to define membership—and the answers often do turn to colonially conditioned historical reference points such as the Dawes Rolls and other such documents. To be sure, these are real and difficult issues here and they are debated intensely, but they are so existential because self-defense against colonial pillaging of Indigenous resources is still necessary in a lot of arenas. Take only the damage done and resources grabbed away from actual Native peoples by white “Pretendians” in academia and other professional fields who claim falsely that they are Indigenous, let alone the phenomenon of entire “race-shifting” “nations” of white people claiming Indigenous status in Canada and the US northeast for themselves. The “fixation” lies first and foremost with the colonial gaze itself, not the efforts of Native communities to grapple with impossible colonial situations. It is to turn the world upside-down to attribute this pathology in a rhetorically almost sui generis fashion to Native peoples’ themselves and to ignore the (many!) efforts that do exist to grapple with such issues in Indigenous communities and in scholarly writing among Indigenous studies scholars.

Ironically, Meaney’s patronizing demand for as much airing of dirty community laundry as possible in the name of exposing the “norm” among Native peoples is as good of an example as I can think of as to why airing dirty community laundry can be so fraught and is so deeply debated in the literature in Indigenous studies. Namely, what if airing those fractures ends up in responses like Meaney’s from white liberals and radicals chastising Native peoples for acting like ordinary human beings dealing with the impossibilities of oppression? As ever, Audra Simpson’s paradigm-shifting work on “refusal” as a practice of Indigenous sovereignty and ethnographic method is on the money here. For, Meaney writes as if these authors are unaware of the many everyday realities of Native politics, or that the authors do not themselves engage issues with contemporary tribal politics, or that there are not other works that do take on these issues. Why not just turn to those other thinkers rather than criticizing historians whose writing is really focused on other areas of research? (For example, Meaney mentions the practice of “disenrolling” tribal citizens to protect scarce benefits. David Wilkins and Shelly Hulse Wilkins co-authored a book on the important topic. Instead of taking these authors to task for failing the litmus test of representativeness, perhaps he should engage with the Wilkins’ and other scholars who do write extensively about these and other issues of contemporary tribal governance? A dizzying number of other works could be mentioned here, especially notable among which is the absence of Indigenous feminists writing from Sarah Deer, Joanne Barker, Mishuana Goeman, Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik, Stark Audra Simpson, Jodi Byrd, Melanie Yazzie, and too many others to name here.)

Misreading Red Power and other Anticolonial Lefts

This brings us back to Meaney’s original framing, in which he describes “examples of Indigenous cooperation with the left” that are not as center stage in these three books. Meaney’s own run-down of these encounters is very good for the most part, and worth reading. Yet surprisingly (or perhaps not so much by this far into reading), Meaney finds Nick Estes’ Our History is the Future wanting as an expression of a left Indigenous politics. Meaney argues that Estes engages in too much romanticization of Lakota history by way of his interweaving of Lakota philosophies in the book. Meaney’s dismissal of this as one of Estes’ interpretive anchors is a bit like dismissing a non-Native leftist for talking about labor by returning to Marx rather than discussing actual labor movements. We can recognize the difference between those two interpretive moves easily enough in those cases, but there is something about non-Native responses to the politics of indigeneity that make this recognition of the gap between structural analysis or aspirational principles and “real politics” incredibly difficult to contend with for those like Meaney.

Indeed, the ideas Estes runs with are not meant to imply that these philosophies perfectly correspond to on-the-ground practice or are that they are even normative with respect to Indigenous peoples, but that they have and do inspire actual Indigenous movement principles. This is why it is so off the mark that Meaney accuses Estes of “wishful presentism,” as if it were in any way in doubt that Indigenous peoples’ philosophies and practices have been at the forefront of defining an anticolonial form of environmental justice politics across the globe. This of course does not mean that any-and-all Indigenous movements are ipso facto anti-capitalist or environmentalist, but, again, we would never even entertain the proposal of such a standard with respect to various iterations of the non-Native labor movement. It would already be well-understood by anyone reading this that the labor movement as it actually exists in places like the United States is riven with conflict and ideologically deeply divided. The principles and values of kinship and relationality that Estes describes have deep historical roots, but they have also been reworked in historical time by Estes and other Lakota scholar-activists as active contributors to those traditions. What Estes is describing is not, as Meaney inveighs, an attempt to place Lakota (let alone Indigenous) historical consciousness outside of history, but instead to reckon with what that history could one day come to mean through the expression of political agency grounded on these normative foundations. Yes, those normative foundations are controversial, but so are all and any.

It is also striking that the arguments Estes makes have much in common with Third World Marxisms such as the Guineau-Bissauian agronomist and revolutionary Amilcar Cabral’s idea that an anticolonial “return to the source” could renew colonized historical agency and help to recapture the national forces of production from imperial degradation. Contra Meaney’s insinuation, it has never been “anti-materialist” in such traditions of anticolonial Marxism to consider the specific and concrete circumstances of a people’s history, including their myths and social and cultural formation as source of inspiration and mobilization. Walter Rodney, a revolutionary hero if there ever was one, understood this as well in his own engagements with the Rastafari movement in the dungles of Kingston, Jamaica. But the context of an already anti-colonial Marxism and left is shoved aside here in favor of an encounter between Indigenous peoples and a “left” already mainly locked into white provincialism. Perhaps it is the fault of such a “left,” not Native movements, that those encounters have been so glancing?

Decolonizing Emancipation

Meaney culminates his essay in the following way, worth quoting at length:

Why suggest the Lakota were self-sufficient, peaceable buffalo hunters in the Black Hills for a thousand years, when they stalked buffalo for less than a century and were so thoroughly connected to international trade that, on entering the homes of their chiefs, visitors found New England carpets, French soap, African coffee, Haitian sugar and knives from Sheffield? What does it mean that the Oneida Nation still celebrates its supporting role in the American Revolution and reveres George Washington, or that a Mohawk man wears a laminated copy of the Fort Laramie Treaty around his neck? Are these signs of freedom or captivity? Nothing could be more patronising to Indigenous peoples than to deny the cost of their survival or pretend that their consciousness exists outside modern time, on a reservation outside history.

But the authors in question pretend nothing of the sort about Indigenous consciousness nor its supposed lack of historically mediated character. (Does Meaney know that the same Estes who wrote the book under review is the co-author of a book on bordertown violence against Native peoples—that most elementary violence of settler-colonial modernity’s traces of history?). It is patronizing to reduce the modes of Indigenous politics, including the many, many articulations of the meanings of treaties and alliances among different Indigenous nations (among themselves and with Euro-american powers) to whether these are signs of “freedom or captivity.” That is, to pretend as if they do not know those costs intimately. But it is this kind ofquestion—what I read mostly as a demand to get in line—that evacuates Indigenous peoples’ varied struggles against settler colonialism of their historical qualities as experienced in colonial modernity, effectively submitting them to a kind of ready-made litmus test of the standards of nominally left politics. Indeed, I find it patronizing in the extreme to fail in the most basic endeavor of trying to understand these modes of politics in their specificity as ways of rethinking what counts as emancipation given the forms of structural power they articulate.

If Meaney has arrogated to himself the implied power to diagnose what counts as the emancipatory (and, therefore, regressive/reactionary) substance in Indigenous politics, I would instead turn the question around: What counts as liberatory in the western left when it is western historical agency—not those of the global majority in the global south and souths in the north—that arrogantly stands in for the motive forces of political emancipation? I submit that what remains is a provincialism consigned to deep irrelevance in the face of today’s pressing needs for anti-imperial and anticolonial solidarities, even when attempting clumsily to escape its own self-referential cage.

David Myer Temin is Associate Professor of Political Science and faculty in the Native American Studies Program, University of Michigan–Ann Arbor.

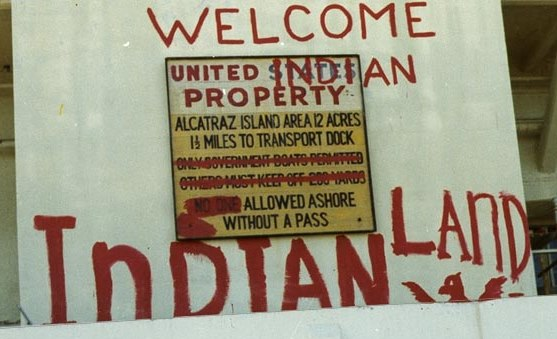

Photo: Graffiti during the occupation of Alcatraz by Red Power activists. Author: National Park Service.

Publisher: Source link