Women have historically been excluded from formal land rights in the Indian subcontinent. For its rural population, land remains the most prevalent and significant asset, making bequests of land parcels the main channel through which women can acquire land (Gazdar, 2003; Nelson, 2011; Agarwal, 1994). Customary land rights prevented inheritance along gendered lines and in colonial times, these laws were codified to prevent the sale and purchase of land parcels (Nelson, 2011). To what extent and how have such gendered patterns of land ownership persisted in different areas of Punjab in Pakistan? To what extent is there path dependence in gendered land ownership? Those are the research questions I’ll tackle in this blog post.

In 2015, the Government of Punjab introduced a series of reforms aimed at enforcing women’s existing legal land rights in the process of inheritance. One enforcement mechanism introduced was making it the responsibility of local revenue officials to ensure that after the death of a landed individual, each heir would be transferred their inherited share in the land parcel by revenue officials even if the family did not initiate an inheritance mutation process. In addition, paper-based land records originating from the era of British colonial rule were digitized and stored in a central database. The new system made it mandatory to conduct in-person biometric verification of all heirs (male and female) of the deceased for an inheritance mutation case to move forward with the official transfer of land parcels. The introduction of these enforcement mechanisms made an historically exclusive inheritance mutation process more inclusive towards women. But fieldwork suggests that previous patterns of land ownership continue to be repeated in Punjab putting women at a disadvantage. In this blog post I unpack some of these findings, which raise questions about land reform alone as the solution to gendered division of land ownership. Instead, I find that the manner in which old patronage structures interacted with the British colonial system has had lasting implications on the way in which land is distributed.

The political economy of patronage and colonialism in Punjab

Punjab can administratively be divided into three parts (see Figure 1) with each region developing its own specific social relationships and norms due to differing experiences with colonial rule. North and South Punjab were allowed to continue with old patronage structures where the landlords acted as intermediaries between the British and the local population whereas Central Punjab was part of a large-scale irrigation project where the British managed day-to-day oversight through multiple layers of local and British government officials (Fox, 1985; Mohnem, 1993). Within Punjab, the different types of rules instituted by the British across the three administrative regions created a pattern of different patronage structures and social relationships which continue to play a role in defining distribution and control over economic resources such as land (Lange, 2003; Fox, 1985). North and South Punjab are historically defined as “landlord areas” due to the settlement of landowners in this region prior to the arrival of the British (Cheema et. al, 2017; Fox, 1985). During their tenure, the British allowed pre-existing landlord-centered institutional structures to remain in place, and these landowners acted as a go-between between the ruling state and the local peasant population. This form of indirect rule was followed primarily because both these regions were deemed unsuitable for large-scale cultivation of crops that could generate revenue (termed ‘cash crops’) for the state due to the poor quality of soil as well as a dependence on variable rainfall as the main water input for cultivation (Fox, 1985). On the other hand, Central Punjab was deliberately designed as a large-scale irrigation project (known as ‘canal colonies’), for the sole purpose of producing high yields of cash crops for revenue generation; this purposeful design was not only applied to cultivation practices but the type and nature of infrastructure to maximize the efficiency of market linkages and transportation of cash crops to both local and international markets (Mohnem, 1993; Fox, 1985). Ultimately, some parts of South Punjab were also incorporated into the canal colonies due to their proximity to the irrigation system (Gilmartin, 1994). The varied historical experiences of these three regions of Punjab coupled with their specific regional attributes has led to the development of differing patterns of access over land by women in these areas.

Figure 1: Administrative divisions of Punjab

Women’s access to land across Punjab

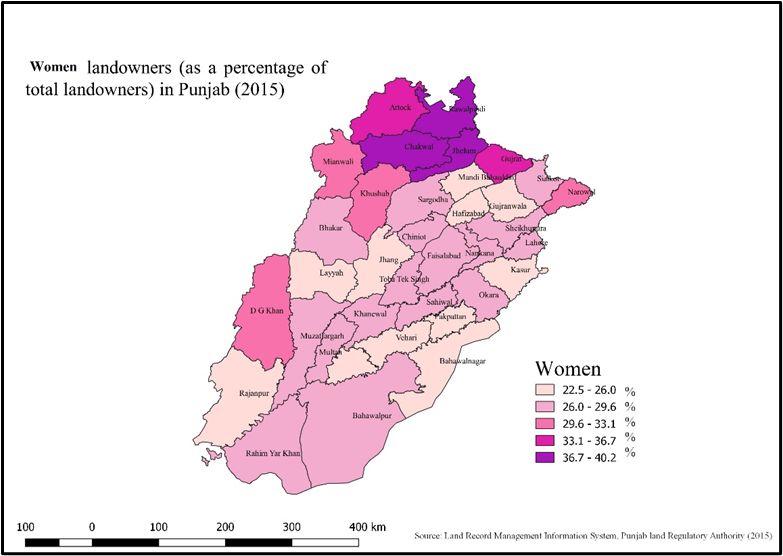

Figure 2 presents a visual mapping of women’s access (proxied by percentage of women landowners out of total landowners in each district) across the province of Punjab. The mapping indicates that access is highest in North Punjab (which is historically a landlord area), and lowest in Central Punjab and areas of South Punjab which now constitute the canal colony parts of Punjab.

Figure 2: Women landowners (as a percentage of total landowners) in Punjab (2015)

Fieldwork conducted with women from landed households across Punjab suggests that households in North Punjab have higher literacy levels as compared to other parts of the province. Landed families in this region (according to the fieldwork) found it difficult to maintain their current lifestyle since land in this region is not very fertile. This led to landed household in North Punjab making alternative investments to increase their wealth, such as education (for both men and women), as well as seeking alternative occupations. With increased opportunities and networks, most landed households in this region have moved away from customary traditions related to land. In comparison, women from landed households in Central and South Punjab remain dependent on their household networks due to low investments made in education coupled with few alternative economic opportunities and networks, leading to the same path dependent relationships for women as their mothers and grandmothers before them. As such, the case of North Punjab indicates that structural changes that shape economic incentives can create opportunities for women from landed households to move away from what might otherwise have led to pathdependent outcomes. As such, it is not that the gendered nature of land ownership necessarily is path dependent, but rather that material conditions shape the extent to which path dependency in land ownership will be maintained.

Dr. Hana Zahir is a Visiting Assistant Professor at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and a PhD graduate of SOAS Economics.

Picture Caption: Crops in Punjab (Pakistan), author’s own

Publisher: Source link